Lucy

C. Ware Webb

Lucy

C. Ware WebbChapter 8

Daughter ~ Lucy C. Ware

With three young children running around the house, all under the age of five, and the colony of Virginia holding its’ breath as tensions rose with Great Britain, it must have been a little overwhelming for Caty when she learned she was pregnant again in 1773. The odds were she was still nursing five-month old baby Polly at the time, and although James was 32 years old, Caty had just recently celebrated getting out of her teens and turning twenty.

The new addition to the family was born on November 12, 1773, and they named her Lucy. The little girl would have been too young to fully understand the ramifications of the Revolutionary War during her early childhood, but by the time she got married in 1790, the war was over and her home was no longer a colony, but a state. George Washington had been elected as the first President, and both her father and fiancé shared the honor of being a “Patriot” for the cause of American freedom.

Lucy

C. Ware Webb

Lucy

C. Ware Webb

Lucy married one year before her older sister, Polly. Her husband was Capt. Isaac Webb; the brother of Charles Webb who would marry her sister in 1791. Both sisters were married in Virginia by the same minister, Reverend Alexander Balmain. (Ref. 307)

In a section written by Thomas Green and quoted in Reverend Hayden’s Virginia Genealogies, it is recorded:

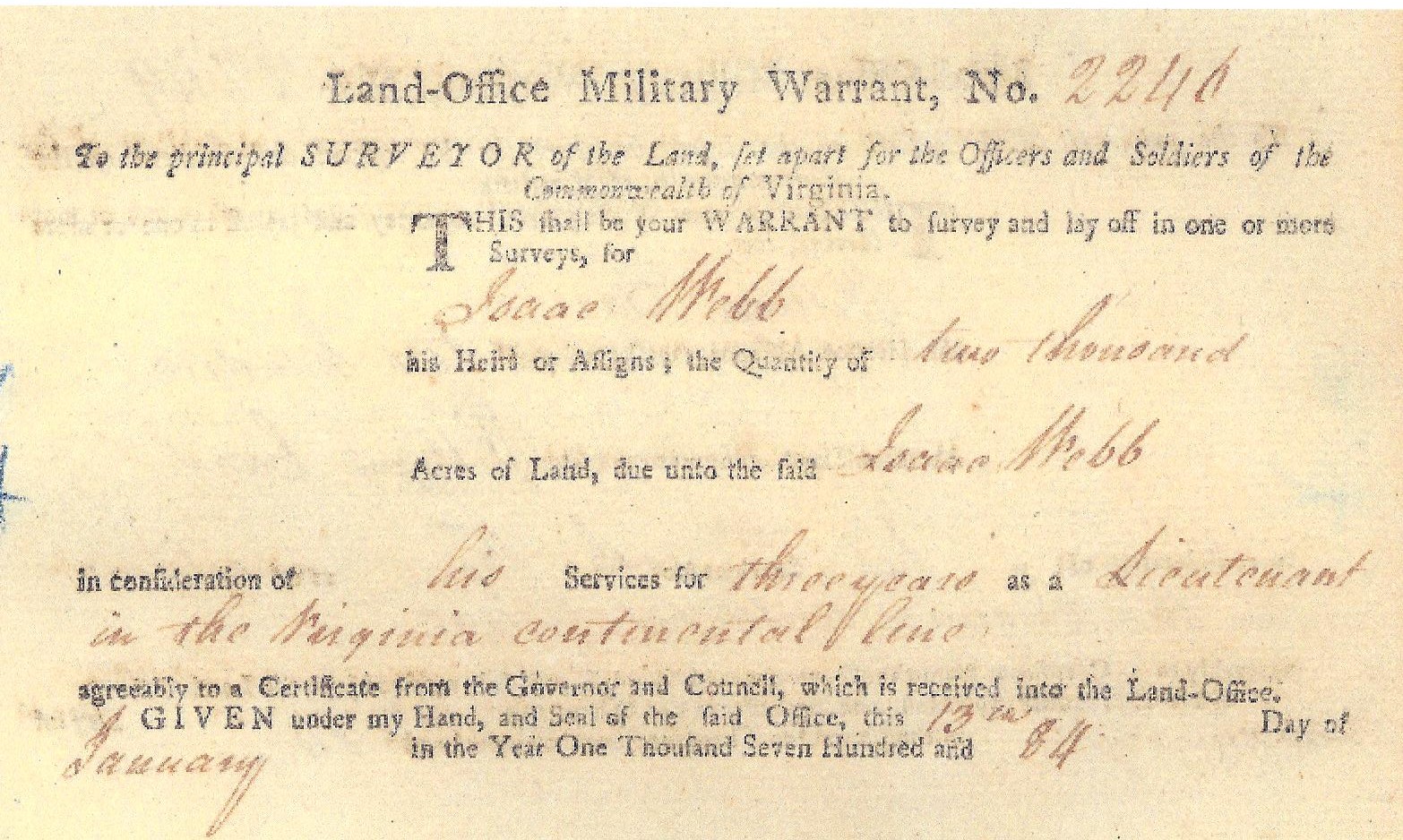

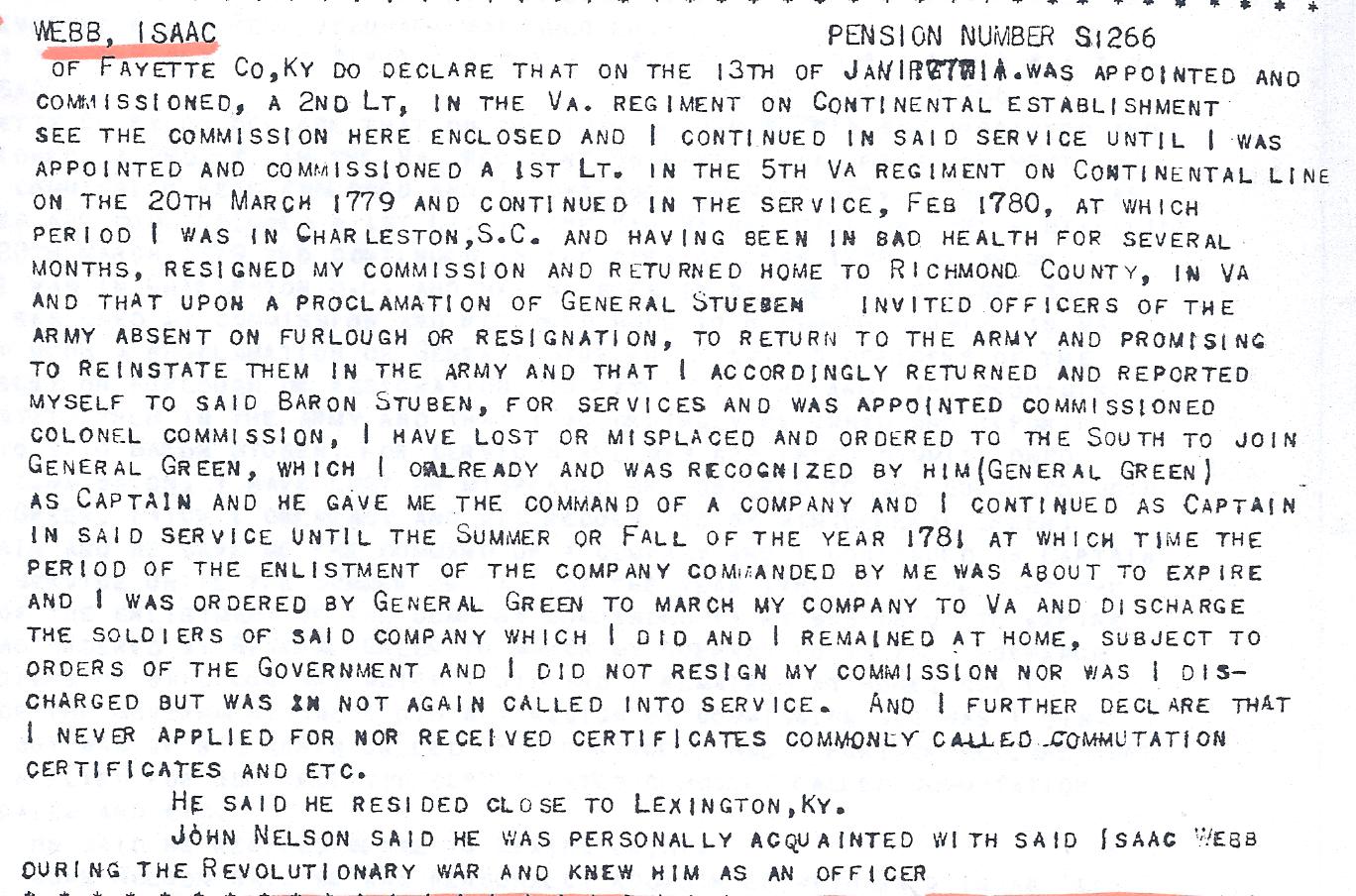

“Isaac Webb enlisted in the Revolutionary Army at the age of 17, served to its close, attained the rank of Captain, and received land from Virginia. ‘Lieut. Isaac Webb, of the Continental line, received Jan. 13, 1784, 2666 2/3 acres for three years service; also an annual pension from May 31, 1833 until his death. He resigned Feb. 24, 1780, after Gates defeat, having served three years and more. General Clinton, by proclamation, offered to reinstate any resigned officer who would repair to headquarters and report. Lieut. Webb at once returned and was made Captain. He marched to the South, with 120 men, and never resigned afterwards.’” (Ref. 6) Actually, Isaac “first served as an Ensign and 2nd Lieutenant in the 7th Virginia Continental Line; then 1st lieutenant, 5th regiment of the Line in 1799.” (Ref. 944) He also “served as a Captain under Green in the 14th campaign.” (Ref. 621,934)

Land

Grant

Land

Grant

Pension record documenting, in his own words, the service of Isaac Webb in the war

Ref.

(943)

Ref.

(943)

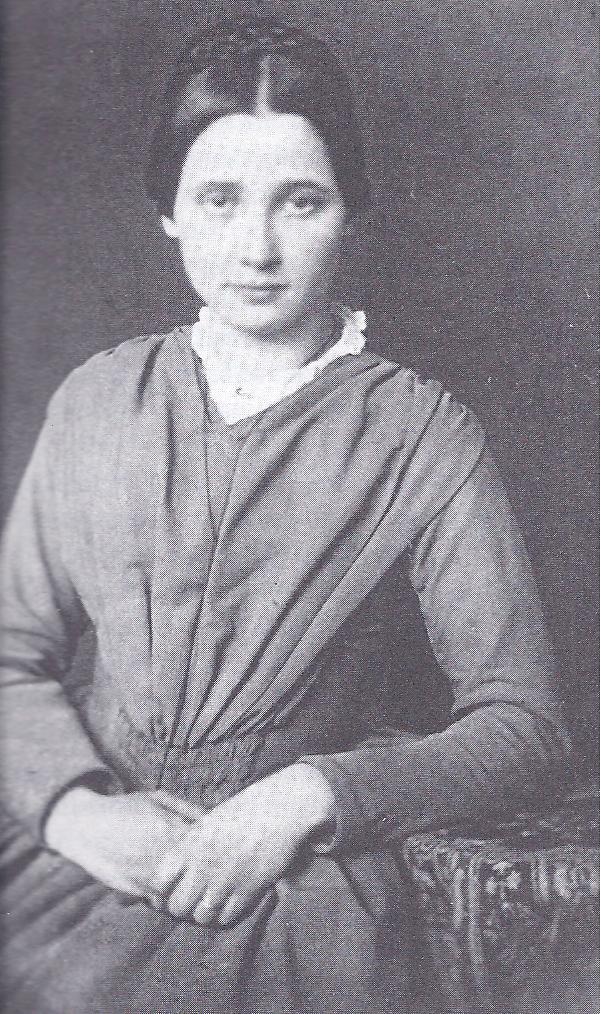

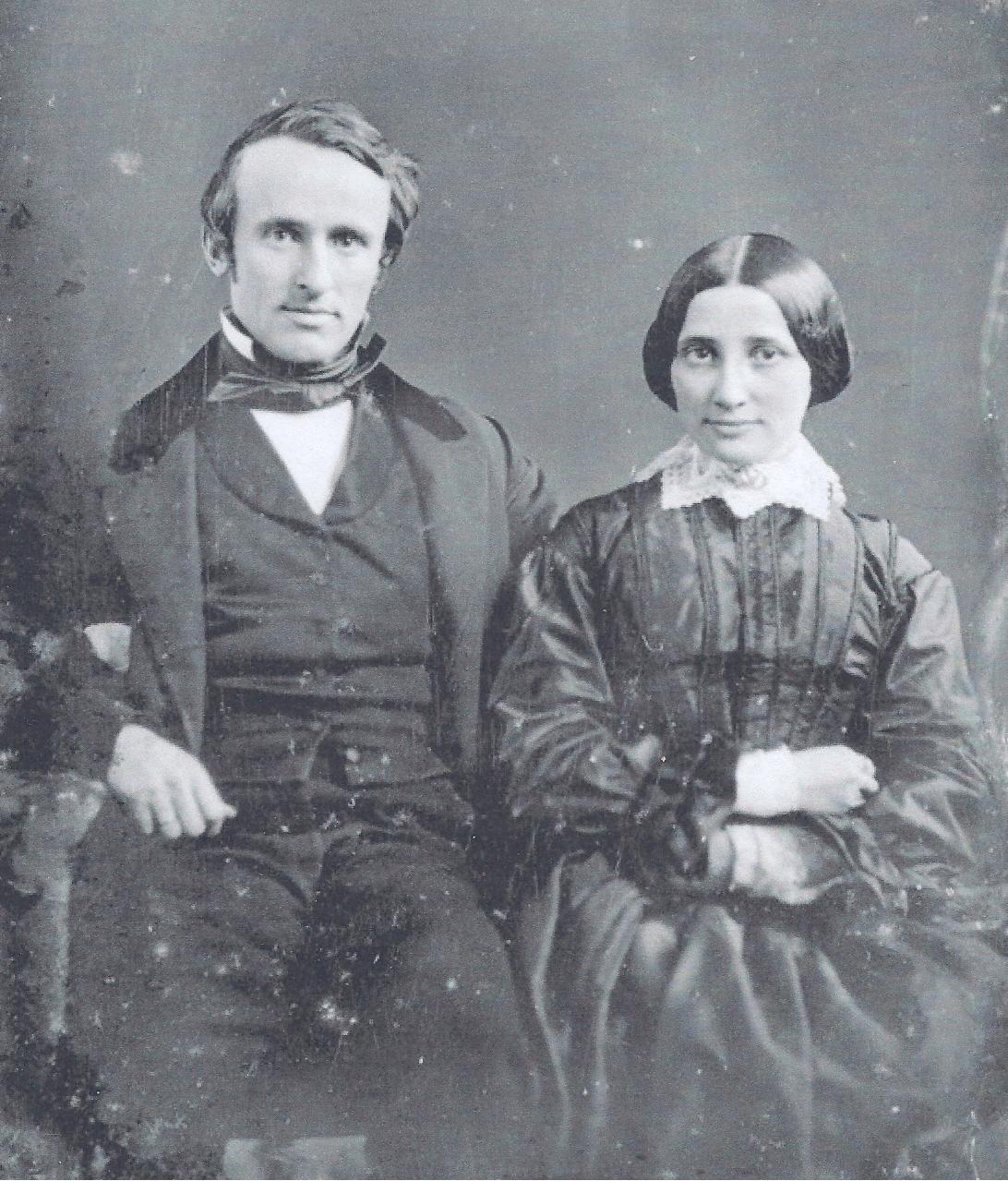

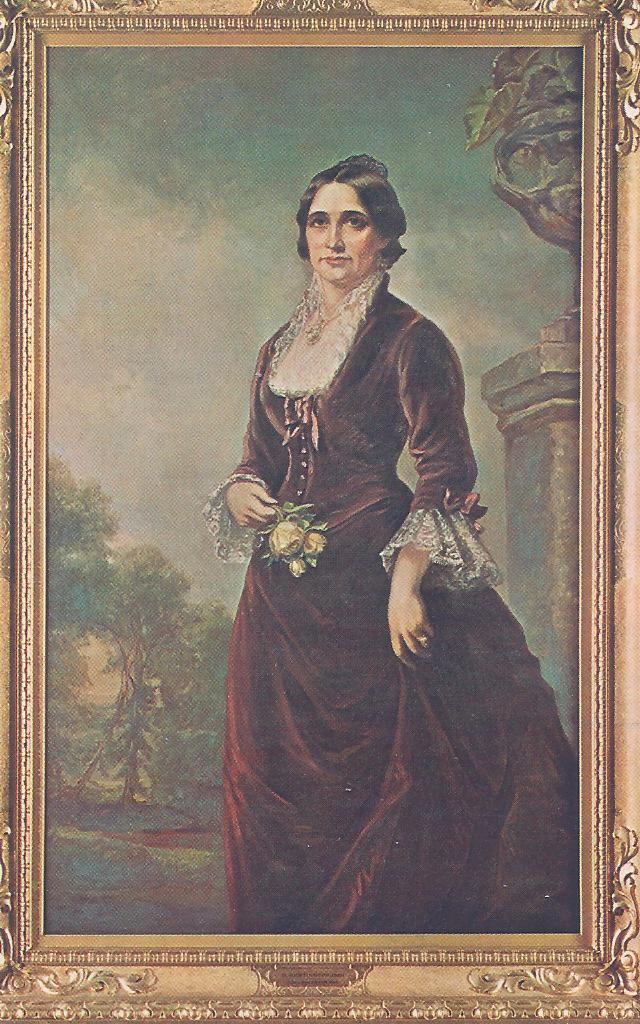

When Lucy and Isaac married on December 23, 1790, Lucy was 17 and Isaac, who was born in 1758, was 32. (Ref. 550, 621, 1067) Josiah Ware, a cousin of Lucy’s, once described Isaac as being “a very small man, of an active figure.” He also went on to add, “I first saw him, at their house near Lexington, Kentucky - - about 12 miles, I think, east of Lexington; about 1825.” (Ref. 174, 638) Josiah, who felt very close to his cousin Lucy, mentioned that she was “very fine-looking; and had as fine a face as you ever saw, full of kindness and benevolence.” (Ref. 638) It is easy to see from the painting of her that she was, indeed, a lovely woman.

James and his son-in-law, Isaac, became close friends in Virginia, and that friendship played a major role in the families moving to Kentucky together. Isaac, having been awarded a land grant by the government for service in the Revolutionary War, “had acquired a great deal of land in Fayette and Bourbon counties of Kentucky.” (Ref. 174) Over 2,666 acres of prime land was nothing to sneeze at. This land, extensively in Kentucky, covered a tremendous area. In a family letter, it was stated that Isaac Webb “owned nearly all the land Cincinnati was built upon and a great part of the land Lexington was built upon.” (Ref. 2) It is interesting to note that the actual land documents he obtained “were signed by both Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.” (Ref. 174)

The Ware and Webb families were now joined by two marriages, making it logical for them to travel together and build their homes in close proximity to each other; thereby claiming vast strongholds in this new “land of promise” called Kentucky. Property was wealth, and the two families now had a lot of Bluegrass acreage.

The land grant for Isaac Webb was described as “a certain tract of land containing 1,000 acres, ‘situate between the Little Miami and Sciota Rivers, north-west of the River Ohio, as by survey, bearing date of the 14th day of May, in the year one thousand seven hundred and ninety-nine, and bounded and described as follows, to wit: Survey of one thousand acres of land on part of a military Warrent, Number Two thousand two hundred and forty-six in favor of the said Isaac Webb) (the whole hereof being for Two thousand six hundred sixty-six and two thirds acres) on the Waters of Paint Creek, beginning at three Elms Southwest corner of John Belfield’s survey No. 1411, and in the line of a survey made for Dowse and Hite No. 1280, running with their line two Hickories and an Elm in Jone’s line thence East four hundred poles crossing a Branch to an Elm and two Honey Locusts thence North four hundred poles to a Stake in a prairie Southwest corner of James Merewether’s survey no. 1127, and South East corner to John Belfield’s Survey thence with Belfield’s line west four hundred poles to the Beginning . . . .”

Patent dated December 22, 1802. (Ref. 174)

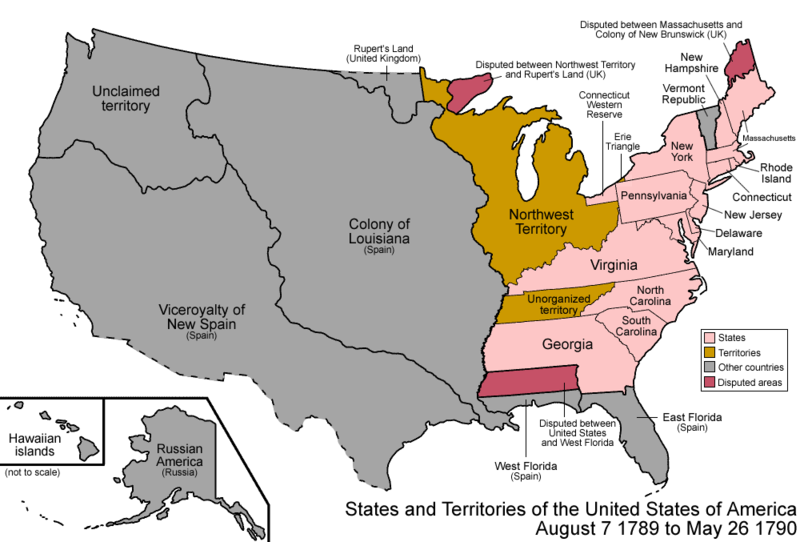

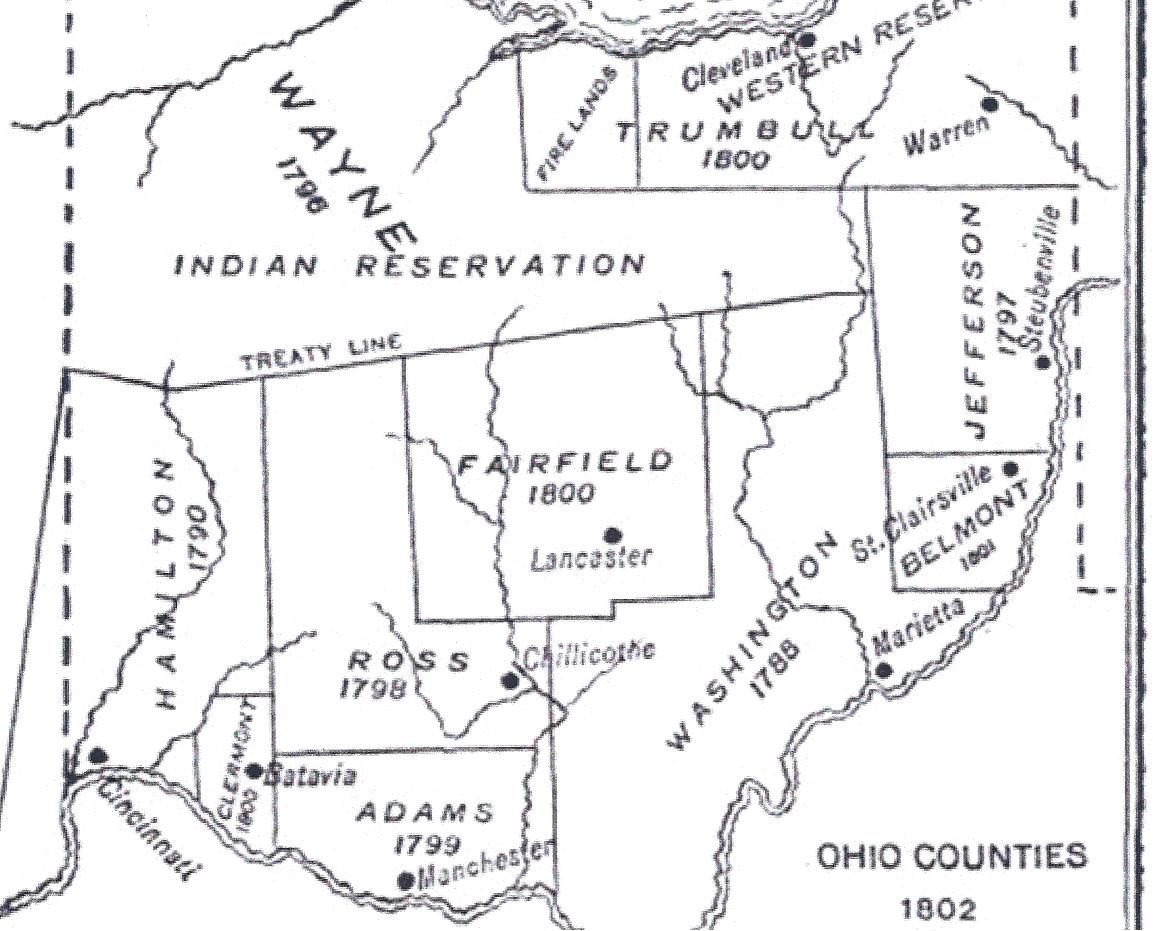

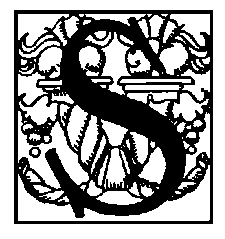

To understand the land grants, it is important to remember that the country looked much different in the 1700’s than it does today. The newly formed Congress, in establishing the Ordinance of 1787, “established the precedent by which the United States would expand westward across North America by the admission of new states, rather than by the expansion of existing states. What was then known as the Northwest Territory was organized out of the region south of the Great Lakes, north and west of the Ohio River, and east of the Mississippi River.” (Ref. Wikipedia ) This was a monumental decision on the part of what used to be the original 13 colonies because it shifted forever the boundaries and powers of each state. It showed tremendous forethought on the part of the nation’s leaders at the time.

According to Wikipedia, “in October 1784, Virginia ceded to the nation the vast territory northwest of the Ohio River, but there were two major stipulations attached to the deal. One demand was that the Northwest Territory had to be divided, eventually, into new states (later determined to be Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and the portion of Minnesota east of the Mississippi River.)”

The second stipulation was that the Virginia Military District, which included the area east of the Little Miami River and west of the Scioto River, was to be used to fulfill land grants promised to those Virginia soldiers who had done service in the Continental Army during the war. The federal government agreed to Virginia’s requests when it accepted the state’s offer of land in 1784.

Article 5 of the Ordinance of 1787 specifically addressed this issue of creating separate states. (See next page)

Maps made by GOLBEZ on Wikipedia

Maps made by GOLBEZ on Wikipedia

The two maps above show how different the state boundaries looked in the 1700s from what they are today. They explain why Isaac lived in Kentucky and yet was also credited with owning land in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Map

showing the location of the border of Kentucky with Cincinnati, Ohio

Map

showing the location of the border of Kentucky with Cincinnati, Ohio

Once the great move was made from Virginia to Kentucky, James and Caty must have been pleased when Isaac and Lucy settled close by. Thompson and Polly put down their roots in the Paris/Centerville area, as did Polly and Charles. Lucy and Isaac, however, chose their land in Fayette County. In fact, the Ware and Webb properties were both located near Antioch Pike.

In a certified statement on file in the Kentucky State Library, W.G. Stannard provided the best existing description of the location of both the Ware and Webb properties:

“I, W.G. Stannard, certify that I have personally examined the records of Northumberland County, Virginia, and that I find the following:

“. . . we come to two brothers who married two sisters, and came from Frederick County, Virginia to Kentucky, in 1792, with their father-in-law, Dr. James Ware. They built three homes on the old Ironworks Pike, just east of the Bryan Station Pike. The Dr. James Ware house still stands at the intersection of the Brier Hill Pike and Antioch Pike (new) and the Isaac Webb Sr. burying ground, also on Antioch Pike, was restored in 1933 by some of his descendants.”

(Ref. 939 )

Map

showing Ware Road

Map

showing Ware Road

Lucy and Isaac did not take long to start their family. By the time the family underwent the strenuous journey through the Kentucky wilderness, Lucy had a young child in tow; her first baby, Catherine Webb, born just nine months after the wedding. Lucy was a fine example of the stalwart women who forged their way into our history books.

Caty was probably thrilled when Lucy’s baby was named after her. Little Catherine (sometimes spelled with a “K”) was born on September 15, 1791. The child was sometimes called Caty, like her grandma, but to help differentiate between the two, she was more often known as Kitty.

Kitty married another member of the Conn family, James Conn. He was the brother of both William Conn (husband of Fanny Webb) and Sallie Conn (wife of Kitty’s Uncle Thompson Ware.) They were married on January 31, 1814, when Kitty was 23 and James was 28. (Ref. 941) Later that year, as the nation was embroiled in the War of 1812, James Conn did his military service. Attaining the rank of captain, he “led a company from September 10, 1814 to October 9, 1814, under the command of Lt. Col. Andrew Porter.”

(Ref. 1055)

Kitty and James had five children; four sons and one daughter. In a letter to her cousin, Sally Ware, on May 6, 1819, Kitty made special mention of her sons: “I have four sons, three living. My first I call John Scott [Conn] after Dr. Scott of Frankfort, my second is named Webb [Conn] after my father, my third is Joseph Scott [Conn] after Dr. Scott formerly of Chillicothe (the doctor is now living in Frankfort), and Thomas [Conn] after Grandfather Conn. My second son, Webb, I had the misfortune to lose (last March was a year) with whooping cough and measles.” (Ref. 35D)

For some reason, Kitty did not mention her daughter in this particular letter, but she and James did have one, named Catherine Webb Conn. On April 14, 1847, “Robert Innes was married to

Catherine Conn, daughter of James Conn & Catherine Webb. They lived in a house on 2nd street in Lexington.” (Ref. 174, 689) Robert had previously been married to Tabitha Boyd. (Ref. 174, 689)

Kitty Conn fell victim to an outbreak of cholera in the early years of her marriage. She died on May 10, 1820. (Ref. 621) Her husband, James, decided to leave Bourbon/Paris County and relocate to Blue Licks in Nicholas County. It is unclear whether Kitty moved with him and died in Nicholas County, or if she stayed in Bourbon County by herself and died after he moved. According to old family letters, she clearly was not overjoyed with James’

From

family bible

From

family bible

desire to move. In a letter written by her mother just prior to 1830, she wrote, “James Conn moved near the blue licks or rocks and mountains; his wife [Kitty] very much opposed to his selling or moving. I have no doubt but it will be his ruin.” (Ref. 597)

James had “inherited the old homestead place of his fathers, but he sold the property to his brother, William Conn, before moving.” (Ref. 941) Kentucky records indicate he relocated “to Nicholas County, Kentucky, where he was living in 1882 and where he probably lived out his life.” (Ref. 941) James did, indeed, stay in Nicholas County. He remarried in 1823 and had four additional children with his new wife, Martha H. (Patsy) Throckmorton. (Ref. Debbie McArdle, wife of James Talbot McArdle, of Crystal Lake, IL.) Kitty’s mother gave a written account of what happened to Kitty’s children after her death. She wrote:

“Kitty’s oldest son, John, is living with James Webb. [James] got me to write to [John’s] father [James Conn] that if he would let him have John, he [referring to James Webb] would educate him and give him whatever professional character his talents would best suit. He sent him [John]. Kitty is living with me. The other two children, Joseph and Thomas, are with him [James Conn] – to my sorrow. I wrote a letter to him [James Conn] the other day that if he would give up their mother’s [Kitty’s] property that Mr. Webb [Lucy’s husband and Kitty’s father] gave her, though it’s but little, we would take the other two boys and educate them and insure to them the property when they came of age. But I did not send it, knowing it would displease him very much.” (Ref. 597) In referring to other grandchildren and how well their parents were looking after their education, she further lamented, “If only other poor motherless ones had the same chance.” (Ref. 597)

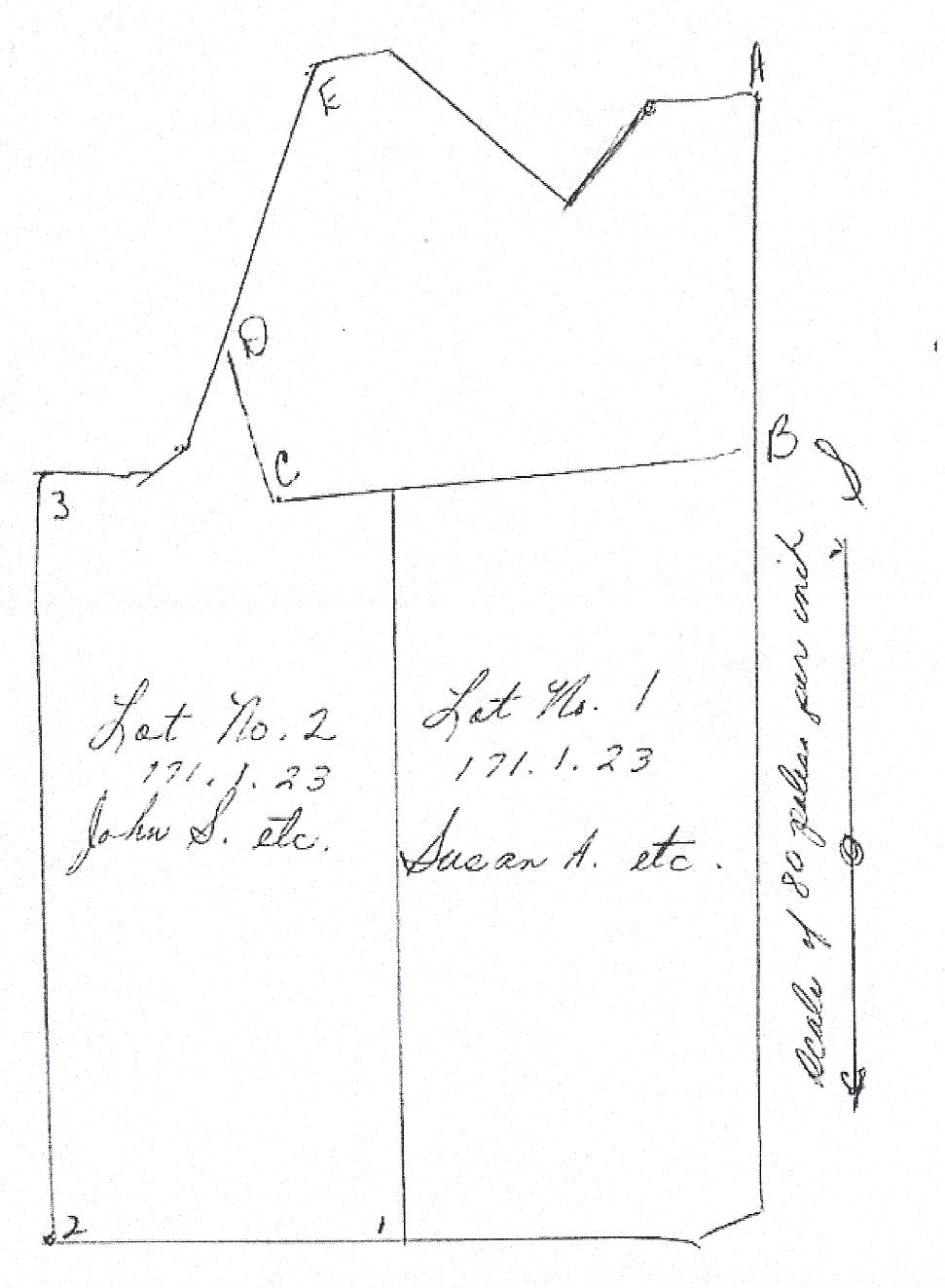

Even though Lucy could not visit with Joseph and Thomas as much as she would have liked, James Conn did provide well, and equally, for all of his children. Papers kindly provided by fellow researcher, Karin Rice, clearly stipulate how much land was to be allotted to each child after his wife’s dower was taken out. (See below)

Chart

given courtesy of Karin Rice (Ref.

2268)

“Lot

#1 went to the children for James’ second marriage, and Lot #2 went

to the children he had with Kitty.”

(Ref.

2268)

“Lot

#1 went to the children for James’ second marriage, and Lot #2 went

to the children he had with Kitty.”

(Ref.

2268)

James Conn died in Nicholas County in 1833. The inscription on his tombstone, which was found by Bill Wheaton in the Throckmorton Cemetery in 1999, reads as follows:

James Conn, Died June 22, 1833, aged 47 years, 1 month, 17 days He died as he lived; a Christian.” (Ref. 2268, 2269)

THROCKMORTON

CEMETERY

Cemetery

is located on Piqua Kentontown Rd. about half way between Piqua

and

Kentontown.

It is on the north side of the road on a farm owned by

Charles

Jackson

and mananged by Elwood Myers. The cemetery is about 60' x

40',

overgrown

with some trees and ivy ground cover.

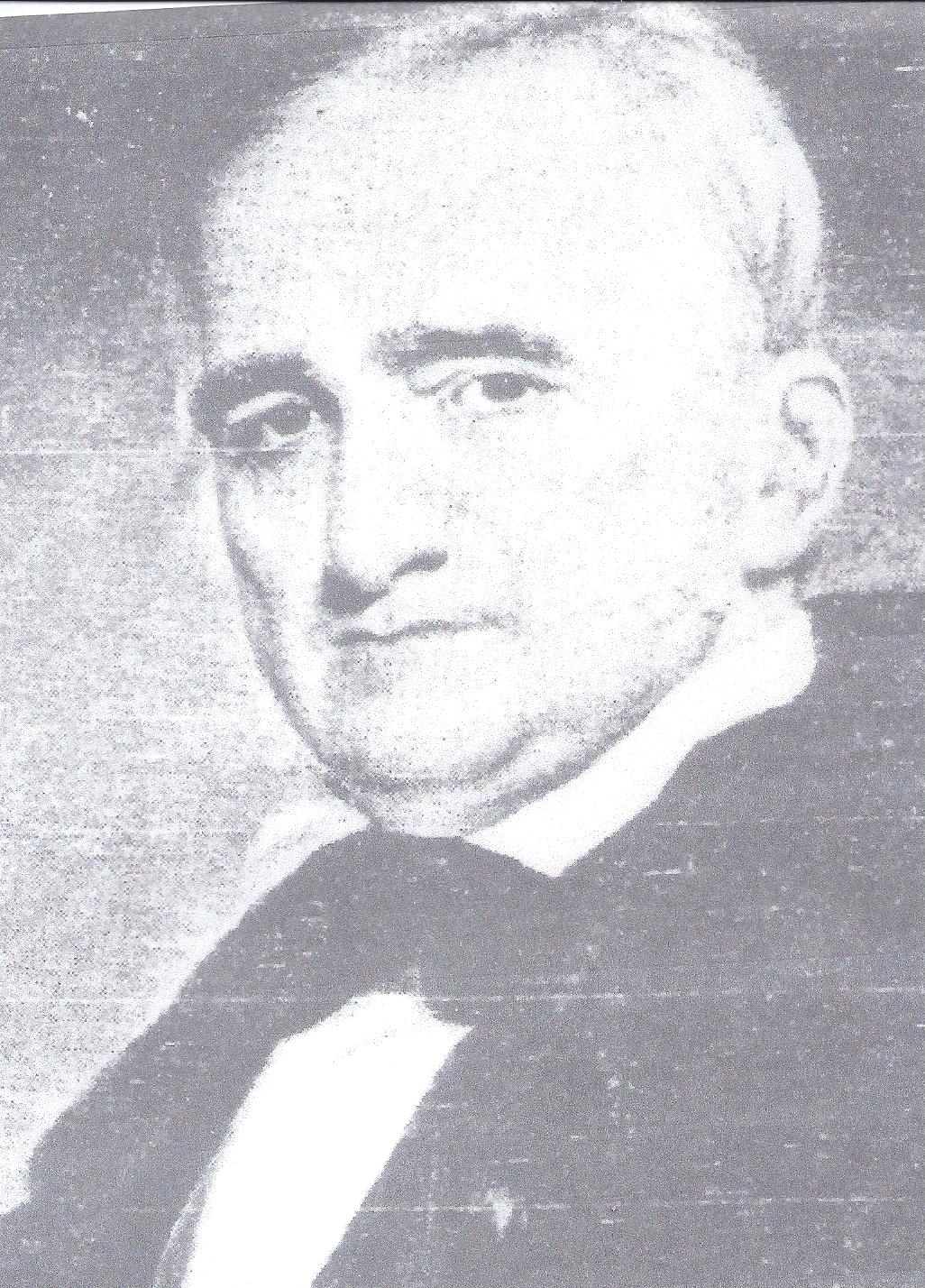

Isaac and Lucy’s second child, another daughter, was born on January 28, 1793. They named her Winifred, but called her Winny. She was probably named after Isaac’s spinster sister, Winney Webb, who was very dear to him. On June 12, 1811, Winny married Mathew Thompson Scott, who was called “Thompson” by family members. In a letter from James Ware II to his son, James Ware III, in Virginia, he wrote, “Thompson Scott was married to Winny Webb the 12th of the month.” (Ref. 35E)

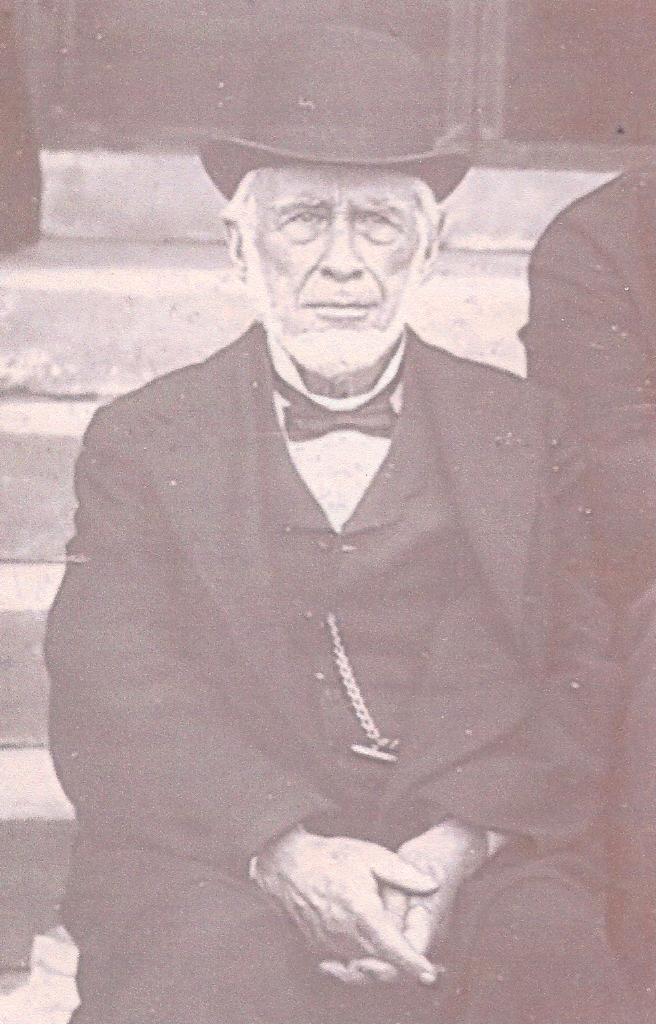

Photo of Mathew Thompson Scott -

Photo of Mathew Thompson Scott -

courtesy of Bill LaBach

Mathew came from a highly respected family in Pennsylvania. “Born in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania in 1786, M. T. Scott lost both of his parents, Matthew and Elizabeth Thompson Scott, when he was very young. He, therefore, came to live with his relative, Dr. John Mitchell Scott of Frankfort.” (Ref. 966, 2261) After settling in Kentucky, Mathew made a fine reputation for himself. “By good judgment, honesty and industry, he attained a comfortable position in later years and during his residence of a half century in Lexington had the respect of the best families in that section.” (Ref. 966)

Just prior to his marriage, Mathew embarked upon a banking career. He “became a clerk in the Lexington branch of the Bank of Kentucky in 1808. After his marriage, he subsequently obtained the position of teller, then cashier, in the United States Bank. When that bank was taken up by Northern Bank of Kentucky in 1835, he became a cashier in the new bank. Mathew Scott became President of the Northern Bank of Kentucky and served in that capacity for six years before his death in 1858. He was also the first treasurer of the Lexington Cemetery Company.” (Ref. 485, 796, 990, 974) The “Kentucky Gazette” newspaper from 1801-1820 lists several business transactions for Mathew:

“Tuesday, August 6, 1811 – Directors of the Bank of Kentucky were elected. Mathew T. Scott is cashier of the Lexington Bank; a promotion from being a clerk.”

“October 13, 1812 – War news mentions Mathew T. Scott at the branch bank in Lexington.”

“Monday, March 27, 1815 – M.T. Scott has stock in Lexington Branch Bank for sale.”

“Friday, June 5, 1818 – The managers of Farmers & Mechanics Bank of Lexington are named, Mathew T. Scott being one of them.”

“Friday, December 17, 1819 – A report given by Mathew T. Scott on the finances of the Farmers & Mechanics Bank of Lexington.”

“Friday, January 14, 1820 – A note from M.T. Scott regarding a statement to the stockholders of the Farmers & Mechanics Bank of Lexington is given.” (Ref. 974)

As his lucrative career prospered, Thompson and Winny watched their family grow. They had 15 children: James W. Scott (1811), Elizabeth (Betsy) Thompson Scott (1813), Isaac Webb Scott (1814), Lucy Catherine Scott (1816), Mary Dewees Scott (1817), Lucy Webb Scott (1819), John William Scott (1821), Winny Webb Scott (1822), Matthew Thompson Scott ( 1823), Margaret Scott (1824), Lucy Ware Scott (1826), Joseph Scott (1829), William Nicholson Scott (1831), and William Thompson Scott (1833). (Ref. 477)

In a letter Lucy Webb wrote to her niece, Sally Stribling, around 1831, she said, “Winny has 11 children living and two dead. She expects to be confined in two months. James, her oldest, is one of the smartest boys. He’ll finish his education this year. Betsy is pretty faced, but too low entirely. Isaac and Mary are going to school in Lexington. Mary is 13 years old; as tall as Betsy now. They are all smart, promising children and will have good opportunity if their father, a man of energy and industry, knows the worth of an education.” (Ref. 597) The pregnancy Lucy made reference to in this letter produced another son. Born on June 20, 1831, the Scotts named the boy William Nicholas. Sadly, the child would only live two years.

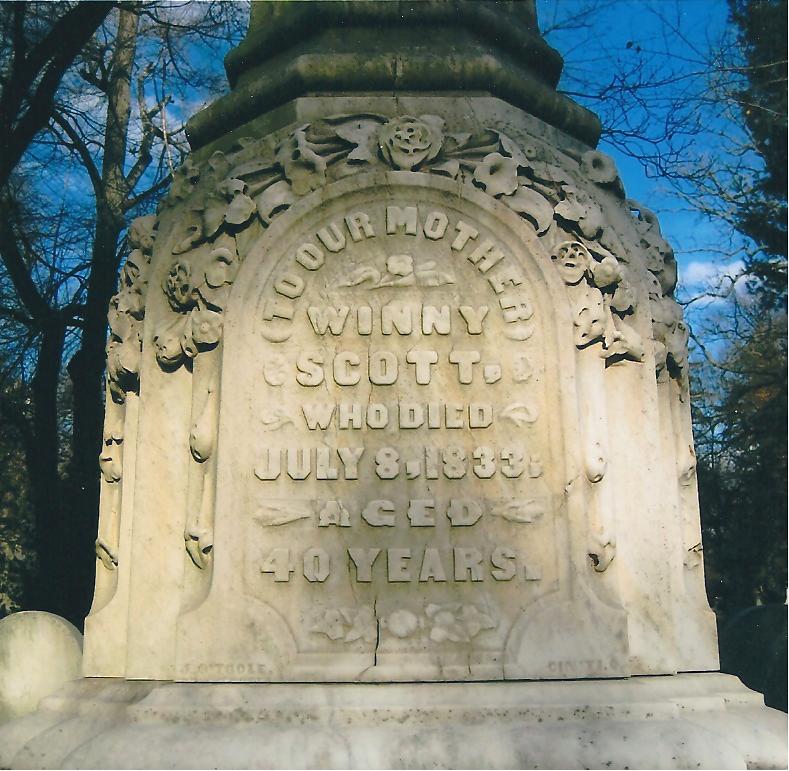

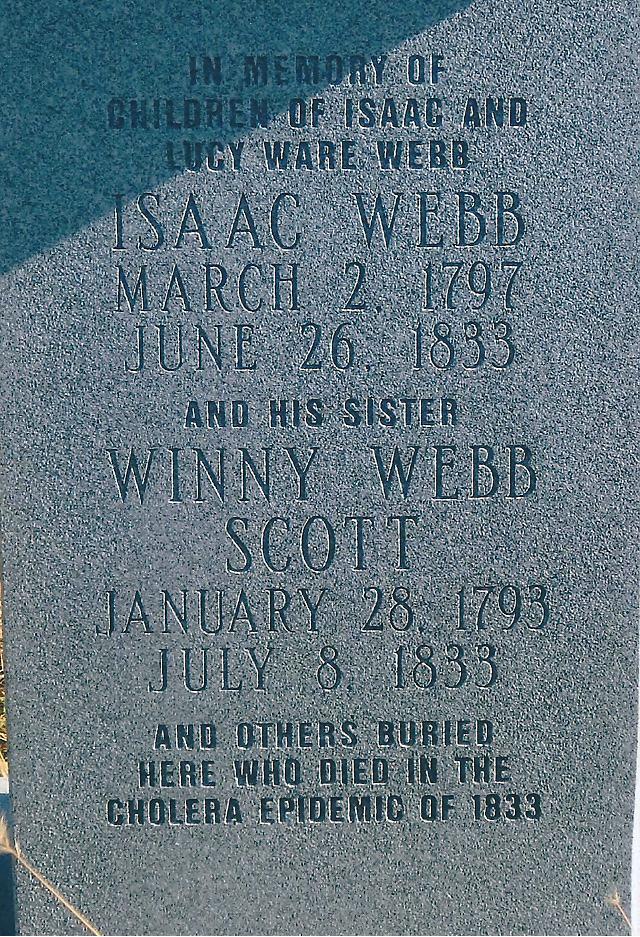

Winny was pregnant again in 1832, but she had no way of knowing how little time she would have with her growing family. Her baby was due in June of 1833, a year that would go down in history as one of Kentucky’s most devastating times. As people would later recall, “the terrible ravages of the cholera in 1833 will ever keep that fatal year memorable in the annuals of Lexington. The devoted city had confidently expected to escape the scourge on account of its elevated position and freedom from large collections of water, but an inscrutable Providence ruled it otherwise. About the 1st of June, the cholera made its appearance, and in less than ten days, fifteen hundred persons were prostrated and dying at the rate of fifty a day. An indescribable panic seized the citizens, half of whom fled from the city, and those who remained were almost paralyzed with fear.” (Ref. 687) It must have been a terrifying time to bring a new life into the world.

There had been a previous outbreak of cholera the year before, so people knew exactly how dangerous this disease could be. “Cholera, an acute, infectious disease characterized by profuse diarrhea, vomiting, and cramps, leads to great body salt depletion. It is spread by contaminated water and food. Major epidemics struck the United States in 1832, 1833, 1849, and 1866.” (Ref. 919) When it came again in 1833, it struck with a vengeance, and by the time the summer passed, the Ware and Webb families were left with little but tears to mark the coming of autumn.

There were reports of the illness striking its deadly blow even as early as May; well before the summer heat had reached its peak. Everyone knew conditions would only grow worse as the summer progressed. Eight months pregnant with another baby, the Scotts had to bear the loss of the little boy they had just welcomed into the world two years earlier. Baby William died on May 4th -- just one month shy of what would have been his second birthday.

Death gives way to new life though, and one month after burying their beloved toddler, Winny gave birth to another son. Still in the grips of mourning, it was probably in little William’s honor that the new baby was named. William Thompson Scott, born on June 23rd, was robust and healthy; so much so, that this tiny infant managed to survive the epidemic that took the life of so many around him.

The Hayes Presidential Memorial Library has a file where the following incident was reported. Mary Ann Todd Webb (Mrs. William T. Nicholson) relayed this story to her daughter, Isabelle Eugenia Nicholson in 1876:

“. . . [In 1833] Sister Winny’s infant was not two weeks old . . . when news came of the death of her parents and her brother reached her. She was kept in so much terror of cholera (because) all the bank officers had died of cholera – (except Mr. Scott [her husband] and one other,) and he was called upon to write wills of persons who had cholera. When Betsey was told of the death of Papa, Mama, & Isaac, she (without thinking) ran into Sister Winnie’s room and said, ‘O, Sister, Ma, Pa, & Isaac are dead.’ Sister lost all reason, though Dr. Scott went to her and said, ‘Winnie, you are not sick but frightened. I assure you, you are not sick’ . . . and when brother was told, he exclaimed in anguish, he ‘had killed them all.’ ” (Ref. 174)

It is certainly not difficult to sympathize with Winny’s great anxiety. Having lost one child already, and now hearing that (not one, but both) her parents and her brother had just died, the shock of the news must have struck fear to the depths of her bones. Sadly, her feelings of doom became reality when she, very shortly thereafter, came down with cholera too.

Winny died on July 8, 1833. She was only 40 years old at the time, and her death left Mathew Scott with a house filled with

Grave marker for Winny Scott

Grave marker for Winny Scott

in Lexington Cemetery

children to rear by himself. Having been orphaned by his own parents at such a young age, he must have felt great sympathy for his offspring. Family members pitched in to help, and Winny’s sister-in-law, “Maria [Cook Webb], took the baby who was William and weaned her own child, Lucy [Lucy Webb Hayes] who was two years old. The cholera was at its height at that time.” (Ref.174) Thompson’s grieving was not over yet, however, as he lost his oldest son, James, to cholera in September.

That year of 1833 was especially terrible for both the Webb and Ware families in Kentucky, with the cholera causing much death and suffering everywhere. Hardly a member of the family was left unscathed, but without a doubt, it would seem the hardest hit was the family of Lucy and Isaac Webb. In a letter to President Hayes from Isaac Scott (their grandson and the son of Winny and Mathew), he wrote in reference to Lucy Hayes’ father and his uncle, James Webb:

“He died at my father’s [Mathew Thompson Scott] house during the terrible scourge of the cholera in July 1833. I sat by his bedside and nursed him during his illness of 8 days and nights, never taking off my clothes as there was so many sick we could not get help. We had four sick at the same time. My mother [Winnie] died a few days before Uncle James.” (Ref. 296)

![]() Mathew

Thompson Scott managed to survive the epidemic and he remarried three

years later. His new wife was another daughter of Lucy and Isaac

Webb. Elizabeth (Betsey) Frances Webb was the youngest sister of

Winnie, and she was twenty years younger than Mathew at the time of

their marriage. They had a very happy and contented life together

before Mathew died on August 20, 1858 at the age of 72.

Mathew

Thompson Scott managed to survive the epidemic and he remarried three

years later. His new wife was another daughter of Lucy and Isaac

Webb. Elizabeth (Betsey) Frances Webb was the youngest sister of

Winnie, and she was twenty years younger than Mathew at the time of

their marriage. They had a very happy and contented life together

before Mathew died on August 20, 1858 at the age of 72.

Grave

of Mathew Thompson Scott

Grave

of Mathew Thompson Scott

Photo taken by James and Judy Ware 2010

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

CHILDREN OF: WINIFRED WEBB and MATTHEW THOMPSON SCOTT

B. Jan. 28, 1793 B. Jan. 5, 1786

D. July 8, 1833 D. Aug. 1858

Winny was the daughter of Isaac Webb and Lucy Ware Webb, and she was the granddaughter of James & Caty Ware. She and Matthew Thompson Scott married on June 12, 1810. When Winny died of cholera in 1833, Thompson married her sister, Elizabeth (Betsy) Frances Webb Cunningham who was also widowed at the time. (Ref. 485)

(1) James W. Scott Born: March 27, 1811 Died: Sept. 07, 1833

(2) Elizabeth (Betsy) Thompson Scott Born: Jan. 21, 1813 Died: April 14, 1835

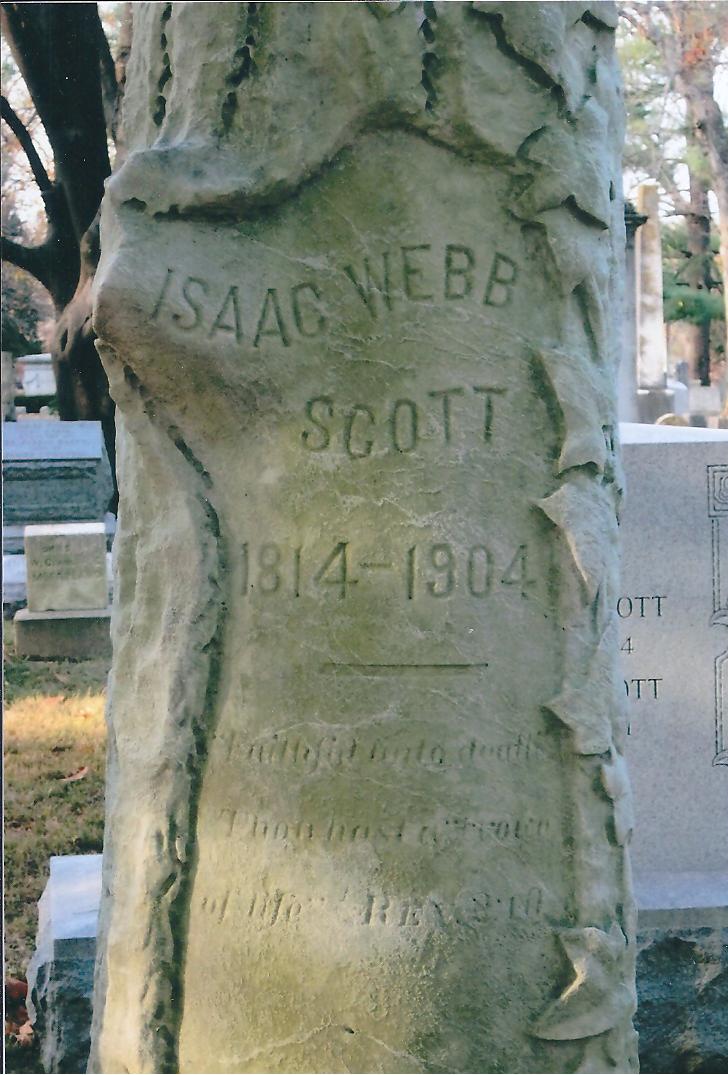

(3) Isaac Webb Scott Born: June 07, 1814 Died: July 28, 1904

(4) Lucy Catherine Scott Born: Jan. 09, 1816 Died: Oct. 13, 1816

Mary Dewees Scott Born: July 21, 1817 Died: Jan. 24, 1902

Married Dr. Dudley

(6) Lucy Webb Scott Born: April 01, 1819 Died: Oct. 12, 1820

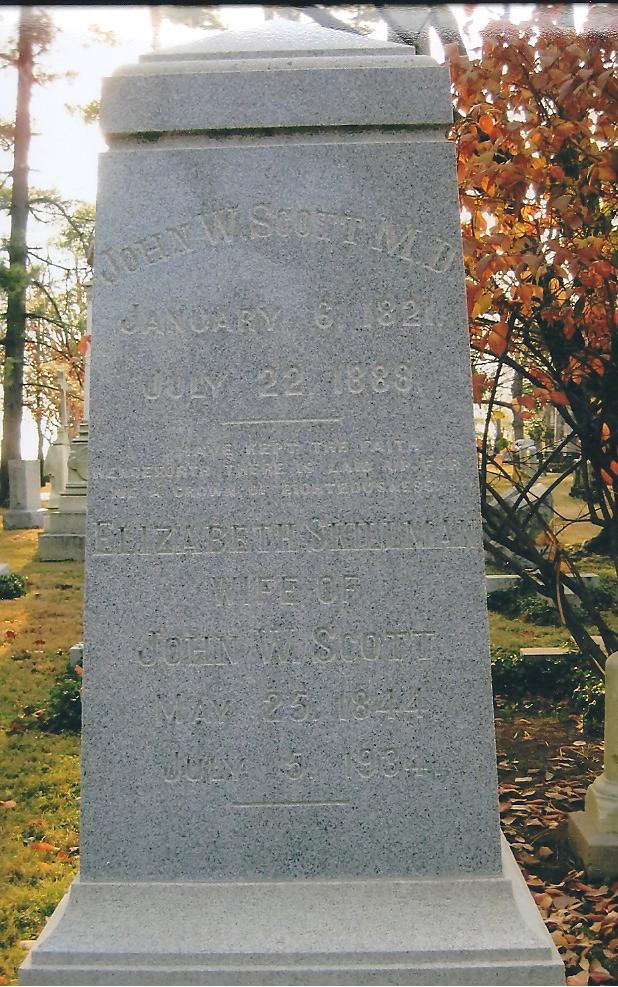

(7) John William Scott Born: Jan. 06, 1821 Died: Jul. 22, 1888

Married Elizabeth Skillman

(8) Winny Webb Scott Born: Aug. 26, 1822 Died: Sep. 27, 1865

Married Charles Gallagher

(9) Matthew Thompson Scott Born: Feb. 24, 1823 Died: May 21, 1891

Margaret Scott Born: 1824 Died: Sep. 24, 1913

Married Dr. Skillman

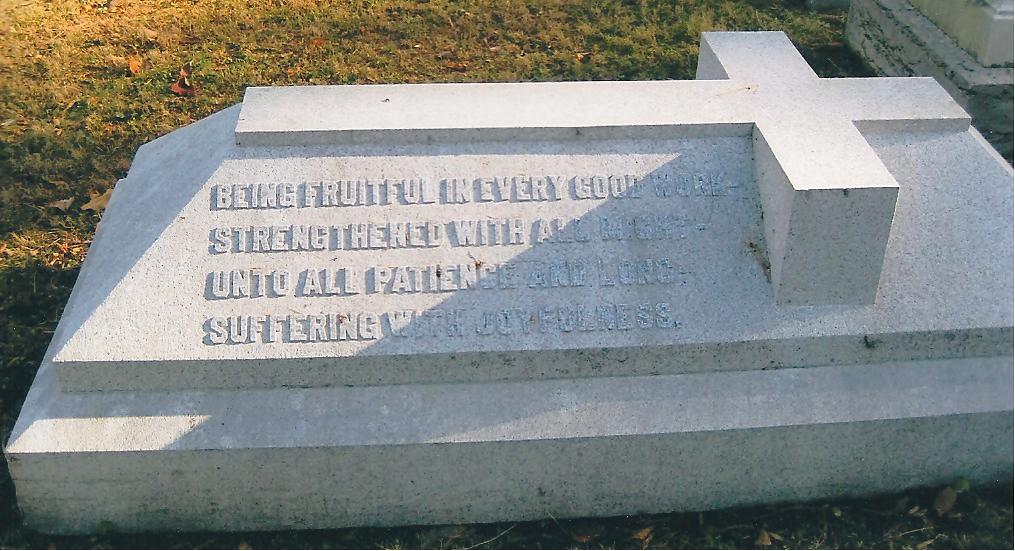

(11) Lucy Ware Scott Born: 1826 Died: Jan. 31, 1901

(12) Joseph Scott Born: April 07, 1829 Died: Sep. 13, 1865

(13) William Nicholson Scott Born: June 20, 1831 Died: May 4, 1833

William Thompson Scott Born: June 23, 1833 Died: Jan. 2, 1875

Numbers above in bold print have a matching photo of the person’s grave below.

(3) Isaac Webb Scott (7) John William Scott

#3 Grave of Isaac Webb Scott

#7 Grave of John W. Scott & his wife

“Faithful unto death, Elizabeth Skillman Scott

Thou hast a crown of life Rev. 2:10

“I have kept the faith, whenceforth there is laid

up for me a crown of righteousness”

#12 Grave of Joseph Scott

#12 Grave of Joseph Scott

Photos taken by James and Judy Ware 2010

Lucy Ware Scott

#11 Grave of Lucy Ware Scott

“Being fruitful in every good work –

Strengthened with all might

Unto all patience and long-

suffering with joyfulness.”

Photos taken by James and

Judy Ware 2010

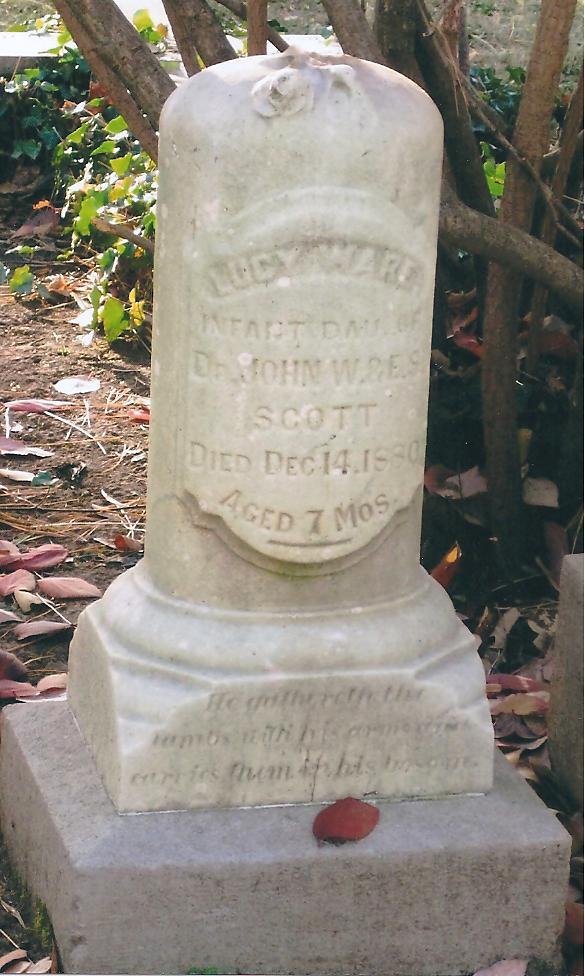

The following two graves are the grandchildren of Winny and Mathew, by their son John Scott and his wife, Elizabeth Skillman Scott.

Grave

of Lucy Ware Scott - Infant daughter of John and Elizabeth Scott-

granddaughter of Winny & Mathew Thompson Scott, great

granddaughter of Lucy and Isaac Webb, and great great granddaughter

of James and Caty Ware She died at 7 months

Grave

of Lucy Ware Scott - Infant daughter of John and Elizabeth Scott-

granddaughter of Winny & Mathew Thompson Scott, great

granddaughter of Lucy and Isaac Webb, and great great granddaughter

of James and Caty Ware She died at 7 months

“He gathereth the lambs with his arms and carries them in his bosom.”

Grave of Bessie Scott - daughter of John and Elizabeth Scott- granddaughter of Winny & Mathew Thompson Scott, great granddaughter of Lucy and Isaac Webb, and great great granddaughter of James and Caty Ware She died at 8 years, 3 months, and 18 days

Lucy and Isaac, thankfully, had no knowledge of what lay

in store for them in 1833, when they had their first son on

Lucy and Isaac, thankfully, had no knowledge of what lay

in store for them in 1833, when they had their first son on

March 17, 1795. They now had a baby boy to carry on the family heritage. They named him James, in all likelihood out of respect for both Lucy’s father and grandfather. Lucy was now 22 years old and big sisters, Kitty and Winny, were four and two years old, respectively.

James studied medicine in Lexington, Kentucky, and practiced in Chillicothe, Ohio. He was a veteran of the War of 1812, having served at the young age of 17. He wed a young lady named Maria Cook on April 18, 1826. In a letter written sometime after 1828, Lucy Webb wrote, “James [my son] is living in Chillicothe, married a Miss Cook [niece of Dr. Scott]. They have two sons, Joseph and James. Miss Cook is amiable but very homely. They are doing, I believe, very well.” (Ref. 597) Maria’s father was Isaac Cook and her mother, Margaret, was described as a “pretty and vivacious local belle” in her younger years. (Ref. 2250) Josiah Ware, a cousin, once noted that “Dr. James Webb was a very handsome man. He had black hair and dark eyes, and was tall and straight.” (Ref. 638) They probably made a striking couple.

James, Maria, and their sons set up housekeeping in Chillicothe, Ohio. “Dr. Webb was educated at Transylvania University and grew up to be a fine type of southern gentleman but with decided opinions in regard to the evils of whiskey, drinking, and slave holding. He and Maria lived in the old Woodbridge house on the corner of Paint and 2nd Street which later became site for Ross County Bank building.” (Ref. 370 & 688)

The couple provided their sons with a sister on August 28, 1831. Their baby daughter was named Lucy Ware Webb, after her paternal grandmother. The young parents had no idea that their little girl was destined for greatness, and James would die before his daughter ever really got a chance to know him.

Ohio home of James & Maria Webb and

Ohio home of James & Maria Webb and

Birth place of Lucy Ware Webb Hayes

Lucy Webb was only two years old when James succumbed to cholera in the 1833 epidemic. She was, however, very close to her grandfather, Isaac Cook, and he proved to be a strong and loving influence in her life. Grandpa Isaac “impressed upon his family, including young Lucy, who adored him, the importance of temperance.” (Ref. 2250) Under his encouragement, she “signed a pledge to forsake drinking any alcoholic beverages.” (Ref. 633) It was a promise she kept faithfully.

Lucy Ware Webb at 16

Lucy Ware Webb at 16

In a time when few women were encouraged to broaden their minds, “Lucy attended the new Wesleyan Female College in Cincinnati at the age of 16.” (Ref. 2251) Nine years older than Lucy, Rutherford B. Hayes was attracted to her bright intellect and inquisitive mind. As a promising lawyer, he had high aspirations for the future which would eventually lead him to become the governor of Ohio and even the President of the United States. Lucy would become the first wife of a president to have a college education. (Ref. 411)

The couple married on December 30, 1852, in Ohio. According to a description of the event, “the ‘radiant’ bride looked beautiful in her white-figured satin dress, simply tailored with a full skirt pleated to a fitted bodice. She wore a floor-length veil, fastened with orange blossoms. It accented the glistening blackness of her hair and the slimness of her figure.” (Ref. 2250)

Lucy’s wedding dress

Lucy’s wedding dress

Rutherford B. Hayes and bride Lucy Ware Webb

Photo from (Ref. 2251)

During the Civil War, Hayes was brevetted a Union major general of volunteers for gallant and distinguished service during the 1864 campaign in West Virginia. Lucy and her husband strongly opposed the South during the war; slavery being one of the many issues the couple agreed upon. Oddly, Lucy’s strong convictions had been fostered by her father and grandfather, both of whom were slave holders at one time. However, “her grandfather, Isaac Webb, Jr., becoming convinced of the evil of the institution, had willed his slaves their freedom and her father, at the time of his death, had been in the process of freeing slaves inherited from an aunt.” (Ref. 2250)

This was one of the numerous examples of how the Civil War often split families apart. Many of Lucy’s relatives in Kentucky and Virginia not only still owned slaves, but fought vigorously on the side of the Confederacy. Never wavering in her belief of freedom for all men, Lucy still grieved for those in her family who suffered loss during the war and, afterwards, during Reconstruction. In her eyes, whether Rebel or Yankee, they were all still “family” when peace finally came.

When the war was over, Hayes decided to pursue his career in politics. After serving as governor of Ohio, he was nominated by the Republican party for the presidency of the United States. It was not a landslide election, but Rutherford won and the couple headed off for the White House with small children in tow. The halls of the capital were often filled with laughter and the sound of children’s voices.

Lucy with three of her children at the White House (Ref. 2250)

Lucy became one of the most beloved first ladies in American history. Her sweet nature charmed all who came to know her. Even though she had her strong convictions on issues such as “no alcohol served in the White House,” the nation fell under her spell. Nicknamed “Lemonade Lucy,” she made no apologies for her beliefs. There were some among the Washington elite who complained at first, but “Lucy’s courage in adopting a controversial policy for White House entertaining helped to convince people of the honesty and

sincerity of the president and the First Lady.” (Ref. 2250) With her tiny stature (she was only five foot, four inches tall), her beautiful black hair, and kind brown eyes, “Lucy Hayes was one of the most personally popular of all of America’s First Ladies.” (Ref. 633, 2251) As one news columnist, Mary Clemmer Ames, wrote, “Mrs. Hayes’s strong healthful influence gives the world assurance of what the next century’s women will be.” (Ref. 2251)

410

410

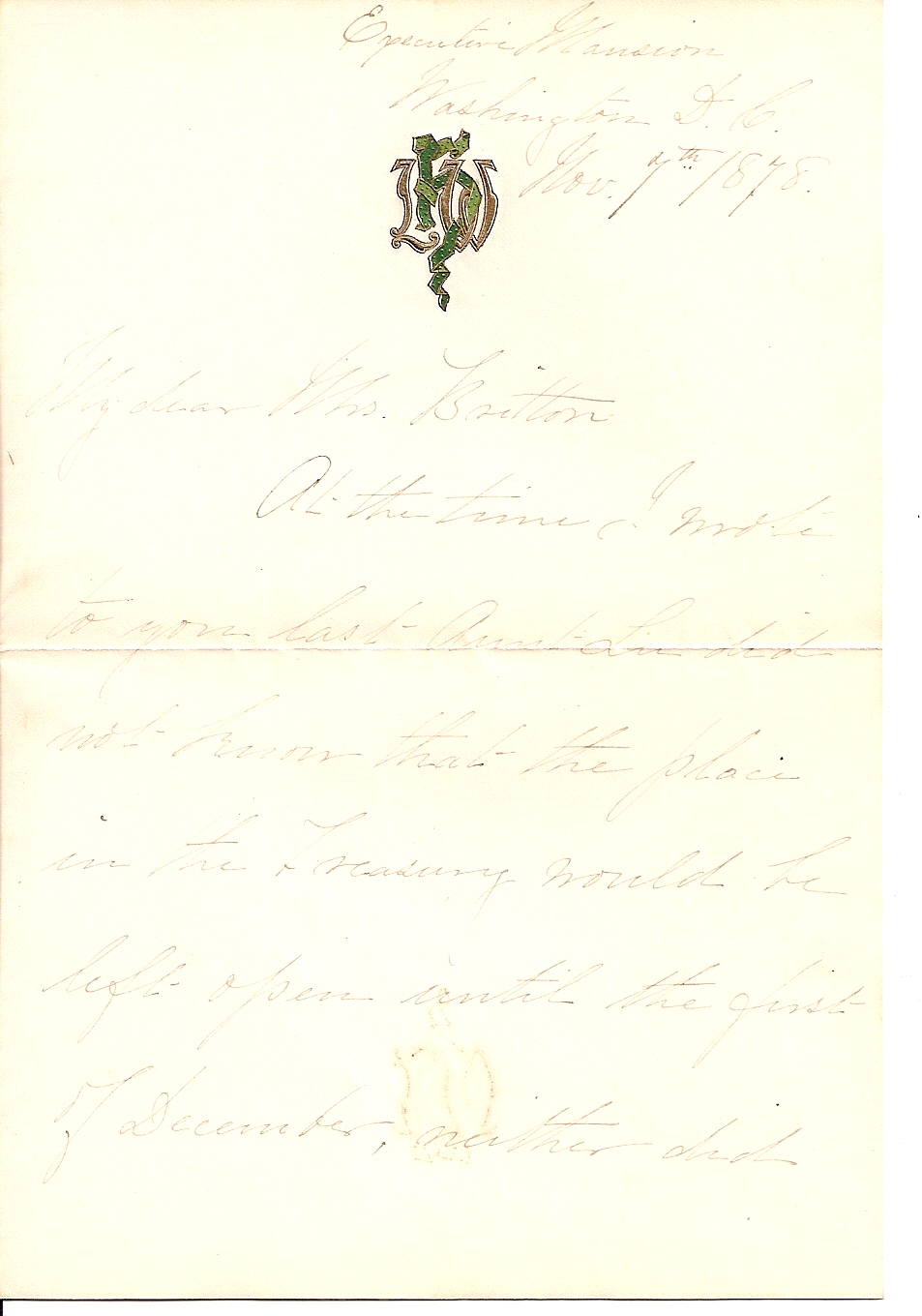

Monogram of Lucy

Monogram of Lucy

Ware Webb Hayes

One of Lucy’s least favorite chores associated with being First Lady was keeping up with correspondence. She was not fond of writing. “Since it was not the custom for a president’s wife to hire a staff of social assistants, Lucy made up for her lack of grown daughters by inviting nieces, cousins, and daughters of friends to assist with social and secretarial duties.” (Ref. 2250) Emma Foote, a cousin from Cincinnati, spent a great deal of time at the White House and helped Lucy with this task of keeping up with the paperwork.

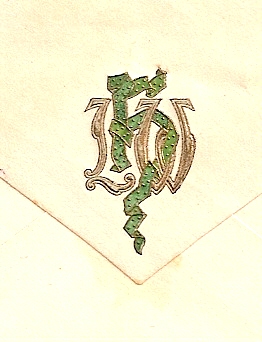

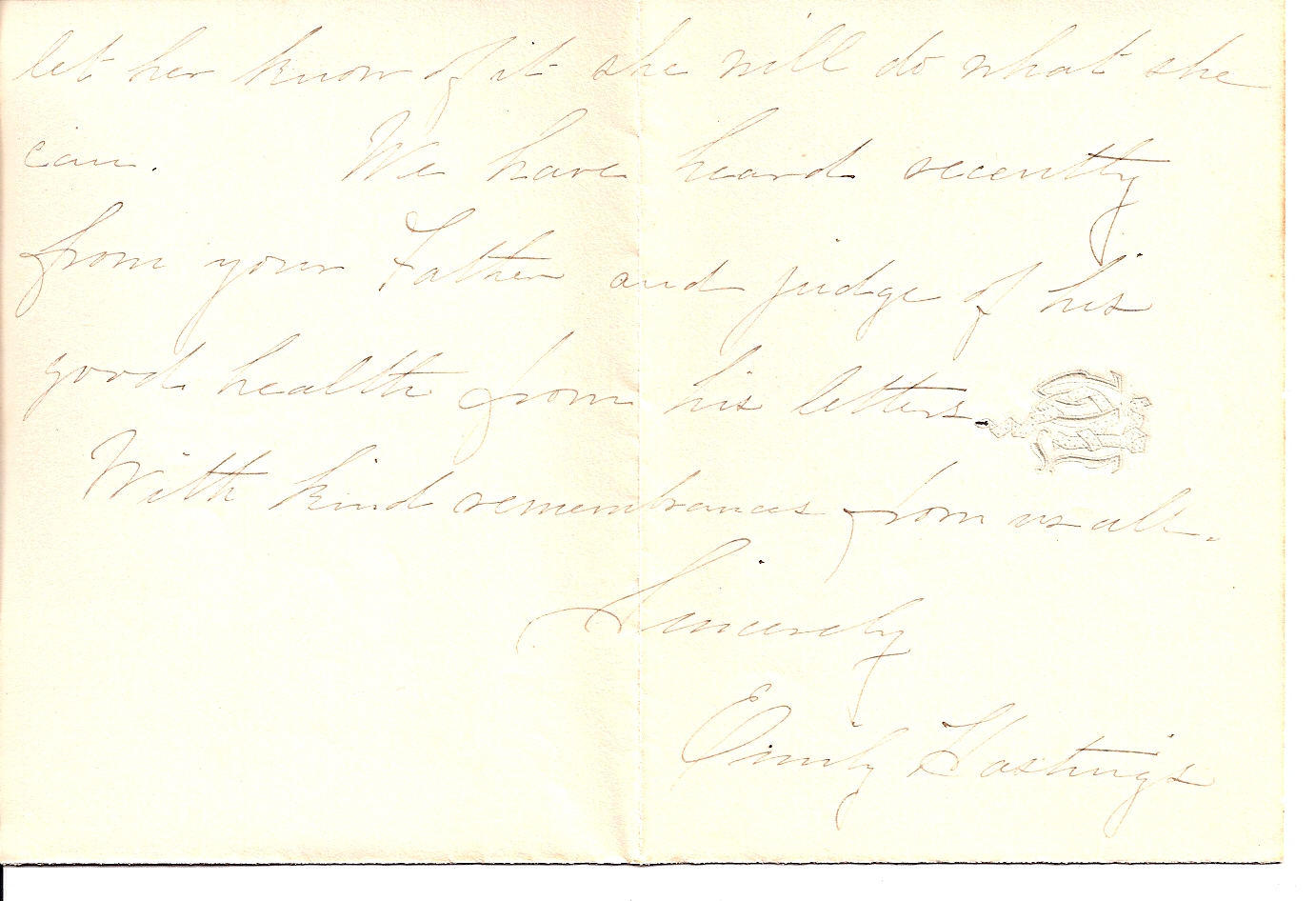

A note to Elizabeth Ware Britton, the daughter of Josiah Ware,

written by Emma Foote at the White House. It is an invitation for

Elizabeth to come and spend the day with Lucy Hayes.

A note to Elizabeth Ware Britton, the daughter of Josiah Ware,

written by Emma Foote at the White House. It is an invitation for

Elizabeth to come and spend the day with Lucy Hayes.

(Ref. 16)

Original note owned by James & Judy Ware

Monogramed note sent from Lucy Ware Webb Hayes at the White House to Josiah’s daughter, Elizabeth Ware Britton, regarding an opportunity for Elizabeth to work in the Treasury Department

Original

owned by James & Judy Ware

(Ref.

17)

(Ref.

17)

Lucy made sure that her home was open to family and friends during her time in Washington. One relative who came to visit several times was her cousin, Josiah Ware, who had owned a large plantation in Virginia before the war. Even though they had been on opposing sides during the conflict, their love for each other remained strong. In fact, there is an amusing story about an incident that happened several years after the war, when Josiah was visiting President and Mrs. Hayes. It personifies the confusing loyalties that were the hallmark of the American Civil War.

Taken from the Memoirs of Thomas Corwin Donaldson

Washington, D.C., April 14, 1882:

“I was chatting with William T. Crump, steward of the White House today, when Col. Ware’s name came up. I have frequently mentioned him. He was a cousin of Mrs. Hayes, and a frequent visitor at the White House; almost a lodger there towards the end of Mr. Hayes’ term. He lived a few miles from Martinsburg, W.V., in a splendid old mansion with beautiful grounds, and attached to it were broad grazing fields. He was sitting one day at breakfast talking with President Hayes, when he described how he saved his estate, houses, herds, etc., until near the close of the war in 1864; and that neither side had touched his Southdowns sheep until that time, which were the finest in Virginia. Crump, who was standing in the room, had been a member of the President’s regiment (23rd Ohio Volunteers) and the President’s orderly during the entire war. He said: ‘Why, Mr. President, don’t you recall we camped near Col. Ware’s place, and our men killed and ate his sheep? Don’t you recall how good the mutton was? I saw you eat some of it. They were killed by your order.’ ‘Well,’’ said the President, ‘I do now recall it.’ Col. Ware and all laughed heartily. It was true Hayes had slaughtered his relative’s sheep. It was a queer place to recall it. Col. Ware afterwards wanted to know if the President would not

recommend his reimbursement by the government. The President declined.”(Ref. 785) There was often such good hearted banter between the two men.

Josiah’s affection for Lucy was apparent in all his writings. At one time, he penned, “I can see a resemblance in the form of Cousin Lucy’s face to Aunt Lucy . . . her eye shows a cheerfulness that was a sweet trait of Aunt Lucy.” (Ref.289)

Josiah William Ware Lucy Ware Webb Hayes

It is easy to see the family resemblance between the cousins; especially around the nose and eye lids.

The Hayes presidency was marked by many new additions to the traditions of White House living. During their time there, bathrooms with running water were installed and a crude wall telephone added. In addition, “Lucy and Rutherford were the first couple in the White House to start the yearly tradition of the Easter egg roll on the front lawn, a tradition that is still carried on.” (Ref. 172, 357)

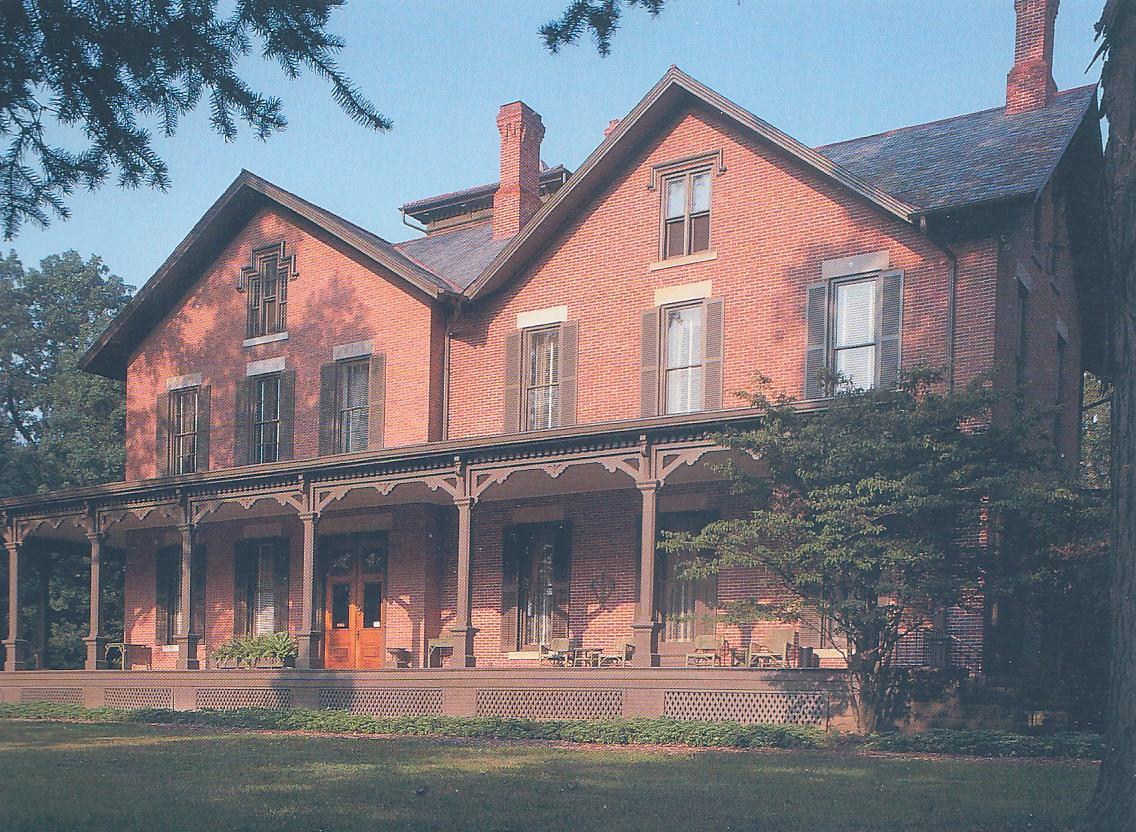

Hayes only served one term in office, and then he and Lucy moved back to their beloved home in Ohio called Spiegel Grove. “Lucy’s passion for social harmony, which had marked her tenure as First lady, continued to influence her actions even after the family relocated. . . Unlike the glass-bowl atmosphere of the White House, where her every move could be observed, however, life in Spiegel Grove, surrounded by a loving family and friends, provided a reasonable degree of privacy and a sense of serenity.” (Ref. 2250)

Rutherford and Lucy celebrated 37 happy years of marriage, spending their final years together in peace and tranquility, each pursuing their favorite hobbies. (Ref. 357,411) Lucy died of a stroke on June 25, 1889, having lived 58 years. (Ref. 357) Her father and both paternal grandparents, having passed away in the cholera epidemic of 1833, never got to know what a remarkable woman she turned out to be.

~~~~~~~~~

Spiegel Grove

CHILDREN OF: DR. JAMES WEBB and MARIA COOK

B. March 17, 1795 B. March 9, 1801

D. July 1, 1833 D. Sept. 14, 1866

James was the son of Lucy Ware Webb and her husband, Isaac Webb. He was the grandson of James & Caty Ware and the great grandson of James and Agnes Ware. He married Maria Cook on April 18, 1826. (Ref. 633)

(1) Dr. Joseph Thompson Webb Born: Jan. 29, 1827 died

Married

(2) Dr. James DeWees Webb Born: Nov. 18, 1828 died

Married

(3)Lucy Ware Webb Born: Aug. 28, 1831 died June 25, 1889

Married President Rutherford B. Hayes on Dec. 30, 1852 (Ref. 411, 633)

CHILDREN OF:

President Rutherford B Hayes and LUCY WARE WEBB HAYES

B. Oct. 4, 1822 B. August 28, 1831

D. January 17, 1893 D. June 25, 1889

Lucy and Rutherford B. Hayes were married on December 30, 1852

(1) Birchard Austin Hayes born: Nov. 4, 1853 died 1926

(2) Webb Cook Hayes born: March 20, 1856 died 1934

(3) Rutherford Platt Hayes born: June 23, 1858 died 1927

(4) Joseph Thompson Hayes born: Dec. 21, 1861 died June 24, 1863 18 mo.

(5) George Crook Hayes born: Sept 29, 1864 died May 24,1866 at 20 mo.

(6) Fanny Hayes born: Sept. 2, 1867 died 1950

(7) Scott Russell Hayes born: Feb. 8, 1871 died 1923

(8) Manning Force Hayes born: Aug. 1, 1873 died 1874 13 mo.

(Ref. 357, 2250)

Members of the Hayes Family on the porch at Spiegel Grove,

around June 1887

Isaac and Lucy Webb had their fourth child on March 2, 1797, giving young James Webb a brother. They named their new son Isaac Webb III, after both his father and grandfather Webb. He married Louisa Harrison Jones and the couple had four children: Lucy Webb (1824) who married Dr. Robert W. Bush; Edward Webb who died, probably of cholera, in 1833; Isaac Webb IV (Nov. 26, 1831) who married Miss Gray and died in 1898; and Frances Webb (1828). In an early letter written by Lucy, she stated, “Isaac has two children; Lucy and Edward [who] live ½ mile from him on Miss Winney Webb’s farm.” (Ref. 597) (She was probably referring to the spinster sister of her husband, Isaac.) Isaac Webb III died on the same day as his father during the raging cholera epidemic.

Children of Lucy and Isaac Webb Sister of Isaac Webb

Grave markers located in the Webb/Ware Cemetery in Kentucky – photos taken by James and Judy Ware 2010

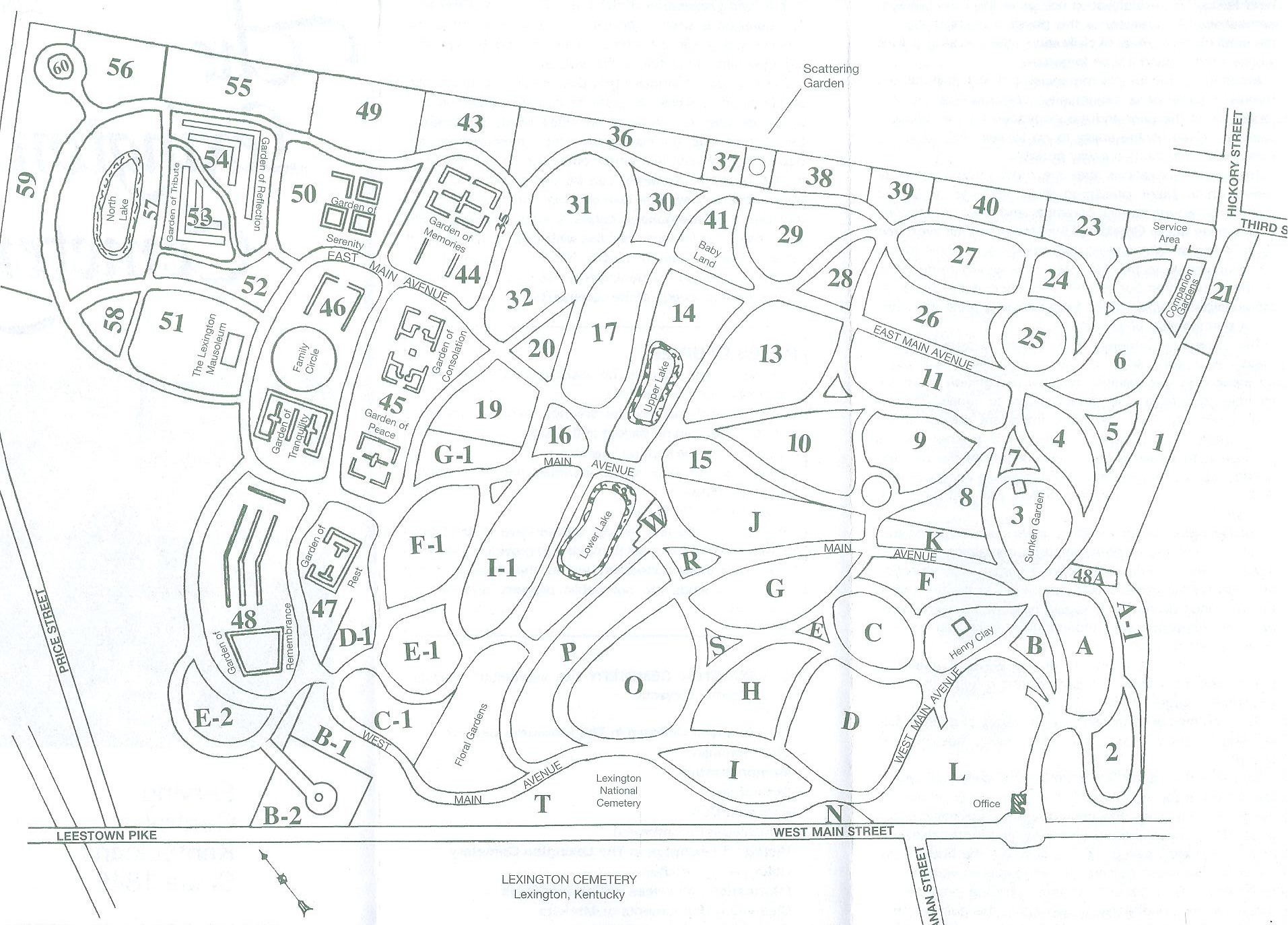

The Webb family continued to grow. On February 16, 1799, Lucy and Isaac added another daughter into the household, this time a namesake for Lucy; her full name was Lucy Caroline Webb. On July 31, 1817, Lucy Caroline became the bride of Dr. Joseph Thompson Scott. Joseph, born in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, was the younger brother of Dr. John Mitchell Scott who had married

Catherine Ware, his bride’s aunt. (Lucy Ware Webb was Catherine Ware Scott’s sister.)

Joseph Scott, as did his brother, had gone into the medical profession; graduating from the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. He set up his early practice in Chillicothe, Ohio, where he met his first wife, Martha Finley. (Ref. 479,805) He and Martha were married in 1805 and they had two daughters before Martha passed away in 1810. (Ref. 482,688) After her death, Dr. Scott took his little girls and moved to Lexington. It was here that he met Lucy Caroline Webb. (Ref. 805)

Known as “an able physician and a man of considerable financial ability,” Dr. Scott married Lucy Caroline “near Bryant’s Station, ten miles from Lexington. The dividing line of Fayette and Bourbon counties ran through her father’s place.” (Ref. 2261) After they were married, “Dr. Scott returned to Chillicothe around 1822. He joined Lucy’s brother, Dr. James Webb, in 1825 and they practiced in partnership for about two years. He was more attracted to Kentucky though, and he and Lucy went back in 1827.” (Ref. 688)

The couple started their own family right away, and Lucy gladly assumed the role of “mother” at the same time she became a new wife, loving Joseph’s daughters as if they were her own. Sarah Finley Scott was 11 years old at the time she gained her new stepmother, and Elizabeth Thompson Scott was just nine. Grandma Lucy wrote to her brother in Virginia that “Elizabeth, the doctor’s daughter by his first wife, is beautiful.” (Ref. 597) The affection Lucy felt for Elizabeth can be seen in her last will and testament, dated 1868. She made this request: “To my step-daughter Elizabeth Fullerton (I give) my breast pin set with pearls and containing the hair of my husband, her father.” (Ref. 449, 451)

Just one year after her wedding, in 1818, Lucy Caroline gave birth to her own first baby. Her little girl bore the name of both her proud mother and her maternal grandmother, Lucy Caroline Webb. This Lucy later married James Montgomery Holloway in 1836 at the age of 18.

Dr. & Mrs. Scott had a baby boy next, naming him Joseph. He was born in 1819 but, sadly, Joseph only lived about a year; dying on September 17, 1820.

The next child born was another daughter. Mary Epps Scott came in the winter of 1821. Grandma Lucy proudly referred to her two youngest granddaughters, Lucy and Mary, in another letter to Virginia. “Lucy and Mary (Epps) are going to school in Lexington – I never saw two children learn faster in my life. Lucy plays the best on the piano that I ever heard one for the time she has been learning.” (Ref. 597)

Mary Epps Scott

Mary Epps Scott

Mary Epps Scott wed John W. McFarland on January 2, 1844. After many happy years of marriage, Mary died before John in 1885.

(Ref.

464) Mary Epps Scott McFarland

(Ref.

464) Mary Epps Scott McFarland

Grave marker

for John McFarland & Mary E. Webb McFarland in Lexington

Cemetery – photos taken by James and Judy Ware 2010

Grave marker

for John McFarland & Mary E. Webb McFarland in Lexington

Cemetery – photos taken by James and Judy Ware 2010

“Asleep until the day break and the shadows flee away”

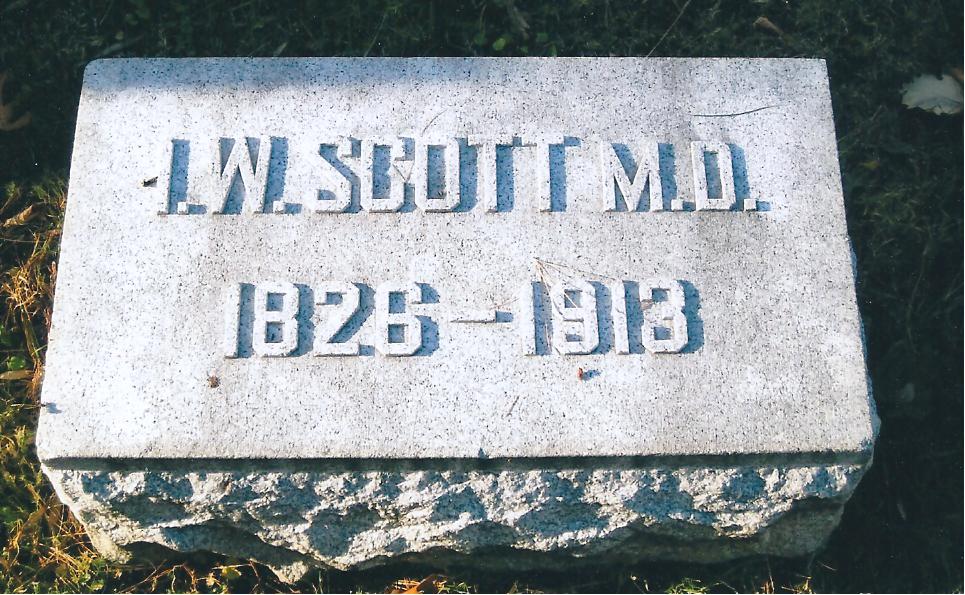

Another baby daughter arrived for Lucy and Joseph on November 4, 1822, but little Margaret Scott only lived a very short time, dying in 1823. It was four years before another child came into the family. This time, a son! Isaac Webb was born on June 27, 1826.

Photo of Isaac Webb Scott Courtesy of Guy Hagan Briggs III (Ref. 945)

He became a doctor, married Mary Buchanan, and they lived in New Orleans, Louisiana. Isaac died there in 1913 at the age of 86.

Cemetery markers in Lexington Cemetery

Photos taken by James and Judy Ware 2010

Little is known about Joseph and Lucy’s next two children. A son, James N. Scott, was born in 1828, and then a baby girl, named Catherine Scott, arrived in 1829. Catherine only lived one year before her death in 1830. James, however, lived to adulthood, married Sara Woodbridge, and they had Lizzie, Lena, and Isaac Woodbridge Scott.

Lucy Caroline had another son in 1832, and they named this baby after her husband, Joseph Thompson Scott. He “was a surgeon in the 1st Missouri Infantry CSA and served on the staff of General Frost.” (Ref. 481) Joseph “was taken prisoner during the war, but was later exchanged.” (Ref. 805) He married Isidora Churchill Dean in St. Louis, but “after the war, Dr. Scott located at New Orleans and soon built up a large practice. He died in 1896 in New Orleans.”

(Ref. 805)

The Scotts welcomed yet another son in 1834; this one named Matthew T. Scott. Before dying in 1862, Matthew also served in the Confederate Army. He “lost an arm in battle and was thence forth known as ‘One-Armed Matt.’ ” (Ref. 174)

Grave of Mathew T. Scott

Grave of Mathew T. Scott

Located in Lexington Cemetery – photos taken by James and Judy Ware 2010

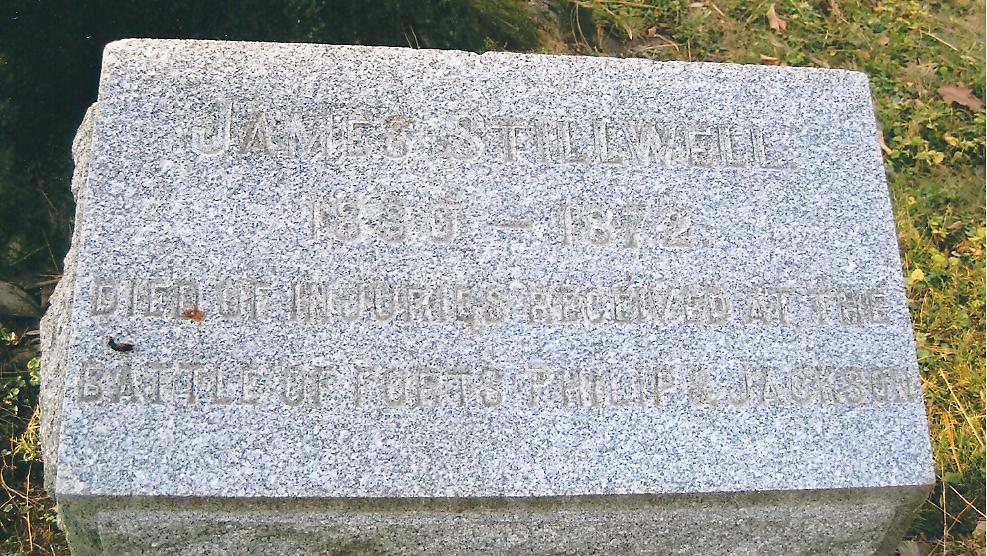

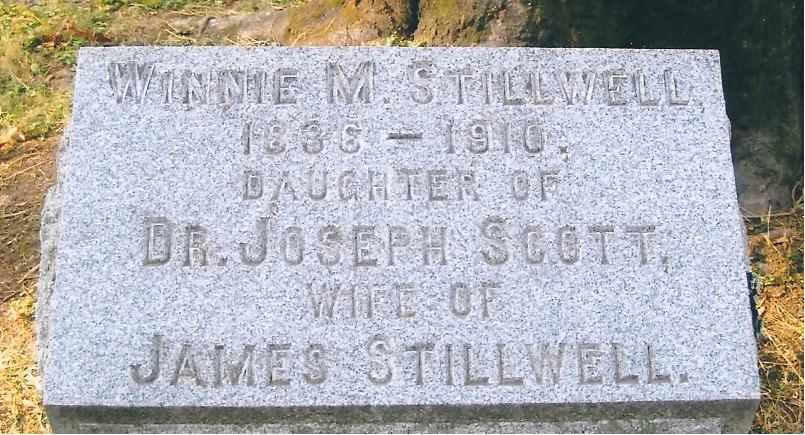

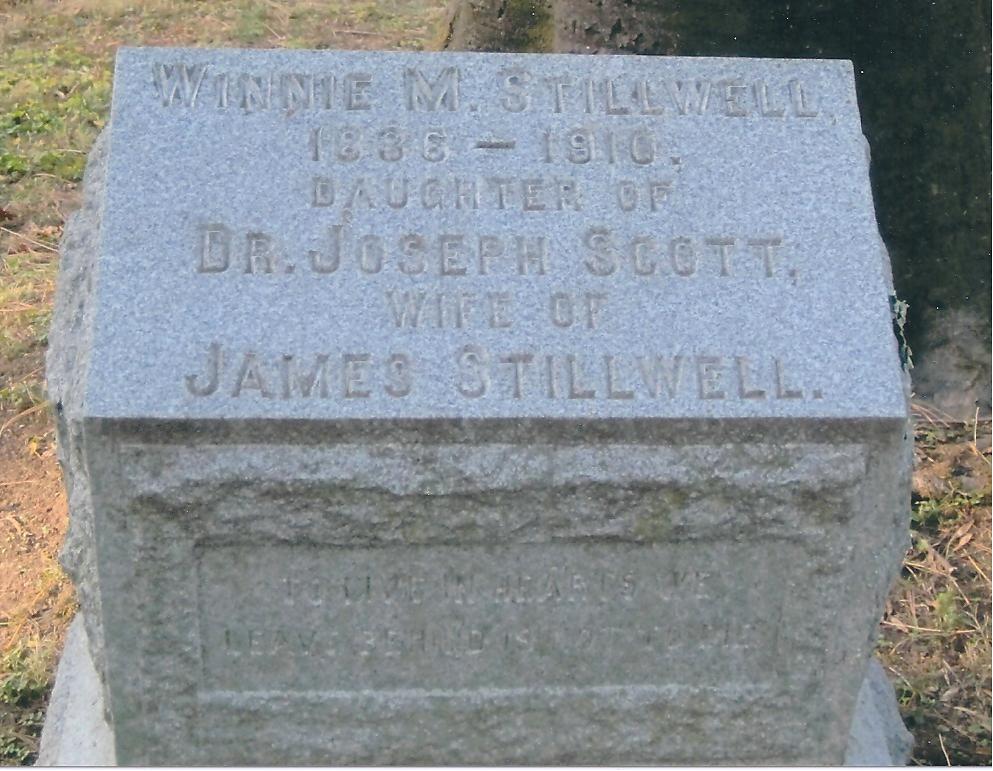

The last two children born to Lucy Caroline and Dr. Scott were Winnie Maria Scott in 1836 and David Humphreys Scott in 1838. Both of these children lived well into adulthood, but not much else is know about them. Winnie married James Stillwell who “died of injuries during the Battle of Forts Philip & Jackson,” and she died in 1910.

James Stillwell grave

James Stillwell grave

Winnie Scott Stillwell grave

“To live in the hearts we leave behind is not to die.”

Graves located in Lexington Cemetery – photos taken by James and Judy Ware 2010

When the Scotts were residing in Lexington, they “owned and lived on a 22 acre tract to be contained within the block now bounded by Limestone Street, Maxwell Street, Rose Street, and the Avenue of Champions (formerly Euclid Avenue). At the time Dr. Scott owned this property, the legal description said it was bounded by Mulberry Street, a line, Van Pelt Street and an alley. Mulberry Street is now Limestone Street and Van Pelt is now Rose Street.” (Ref. 479, 796)

Dr. Scott was loved by the residents of Lexington, and he and Lucy Caroline spent many happy years there. When he died on June 6, 1843, his obituary appeared in the “Protestant and Herald” newspaper, and was reprinted in “The Frankfort Commonwealth” of June 20, 1843. It read as follows:

"It becomes our painful duty to record the death of our very highly esteemed friend and excellent fellow citizen, Dr. Joseph Scott, of Lexington, who departed this life at his residence, on Tuesday, the 6th inst., at about 10:00 p.m. Dr. Scott was born Feb. 19th, 1781, lived sixty-two years, three months and eighteen days, and then 'slept with his fathers'. He has been long and most favorably known in this State and in Ohio, as one of our ablest and most successful Physicians. Diseases, often of the most malignant character, were made to yield, with the blessing of God, under his superior skill, and even death, in some instances, where he had apparently commenced his work, was staid, and the tide of life and health restored. Many, very many of the living will bless his memory while they retain their recollection. His funeral was attended by the largest and most respectable class of citizens we have ever witnessed on a funeral occasion in Lexington. Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Methodist and Baptist, with scores of non-professors of religion, attended with demonstrations of the deepest feeling and solemnity. The funeral procession was of great length; scores of carriages, and persons on horse-back, and the sidewalks of the streets crowded with people on foot, all slowly, silently and solemnly following the remains of their departed friend to the last lodging place of mortals - the grave." (Ref. 482)

![]()

Joseph was 62 years old when he died. Lucy, at 44, would remain a widow for 25 years before her own death in March 1868.

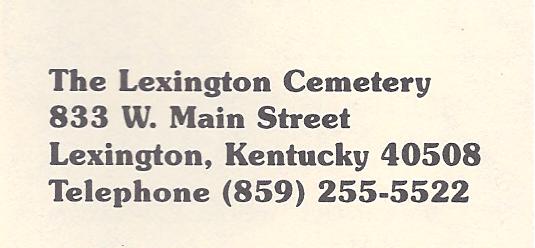

Grave of Dr. Joseph Scott & Lucy C. Webb Scott

Photos courtesy of James & Judy Ware 2010

Map showing the layout of the Lexington Cemetery

Lucy C. Scott’s Will

(Ref. 449, 451)

CHILDREN OF:

LUCY CAROLINE WEBB and DR. JOSEPH THOMPSON SCOTT

B. Feb. 16, 1799/1800 B. Feb. 19, 1781

D. March 17, 1868 D. June 6, 1843

Lucy was the daughter of Isaac and Lucy Webb and the granddaughter of James and Caty Ware. She married Dr. Joseph Thompson Scott on July 31, 1817.

He already had two daughters from a previous marriage with Martha Berkley Finley whom he married in 1805. (Ref. 174,482)

(1) Sarah Finley Scott Born: Nov.27, 1806 Died

Married David C. Humphreys on Oct. 7, 1825

(2) Elizabeth Thompson Scott Born May 10, 1808 Died March 6, 1876 Married Humphrey Fullerton on Oct. 31, 1833

AFTER MARTHA DIED, LUCY & JOSEPH HAD THE FOLLOWING:

(1) Lucy Caroline Scott Born: May 2, 1818 Died: Feb. 2, 1897 in Missouri

Married Dr. James Montgomery Holloway on Sept. 22, 1836

(2) Joseph Scott Born November 25, 1819 Died Sept. 17, 1820

(3) Mary Epps Scott Born: Feb. 18, 1821 Died: 1885

Married John W. McFarland on Jan. 2, 1844

(4) Margaretta Scott Born: Nov. 4, 1822 Died: Aug. 18, 1823

(5) Dr. Isaac Webb Scott Born: June 27, 1826 Died April 11, 1913

Married Mary Buchanan

(6) James Nicholson Scott Born: March 17, 1828 Died: 1867

Married Sara Woodbridge on Jan. 6, 1853

(7) Catherine Scott Born: Nov. 2, 1829 Died: Dec. 28, 1830

(8) Joseph Thompson Scott Born: March 20, 1832 Died Jan. 25, 1896

Married Dora Churchill Dean on Dec. 2, 1856

(9) Matthew T. Scott Born: Jan. 2, 1834 Died July 7, 1862 in the Civil War serving in the Confederate army; known as “One Armed Matt”

(10) Winnie Maria Scott Born March 20, 1836 Died: 1910

Married Capt. James Stillwell, U.S. Navy

(11) David Humphreys Scott Born: Dec. 28, 1838 Died: April 8, 1870

(Ref. 479, 783 & 796, 2261)

In 1801, when Isaac Webb was 43 and Lucy was 28, they celebrated the birth of another son. Cuthbert Webb was born in the cold, wintry month of January. Sometime prior to 1830, his mother wrote, “My son, Cuthbert, lives this year with Dr. Scott, as Lucy (her daughter & Dr. Joseph Scott’s wife) was so lonesome since he moved to the country.” (Ref. 597) Cuthbert was the only adult child of Lucy and Isaac who remained single. Former director of the Rutherford B. Hayes Center, Watt Marchman, established that “Cuthbert never married. It appears that Mary Ann, brother Cuthbert, and daughters Eugenia and Elizabeth C. all settled in the St. Louis area of Missouri.” Other records, kept at the Hayes Library, state that “Cuthbert Webb died at the residence of his sister, Mrs. Nicholson in Missouri. He had inherited 5 Negroes from his Aunt Winny Webb.” His death occurred in 1860.

By the early 1800s, Lucy and Isaac had a house full of children, and they were not through yet. It must have delighted James and Caty Ware to have so many grandchildren around. Kitty was 11, Winny, nine; James, seven; Isaac, five; Lucy Caroline, three; and Cuthbert, one. Another baby girl named Mary Ann Todd Webb joined them on March 15, 1803.

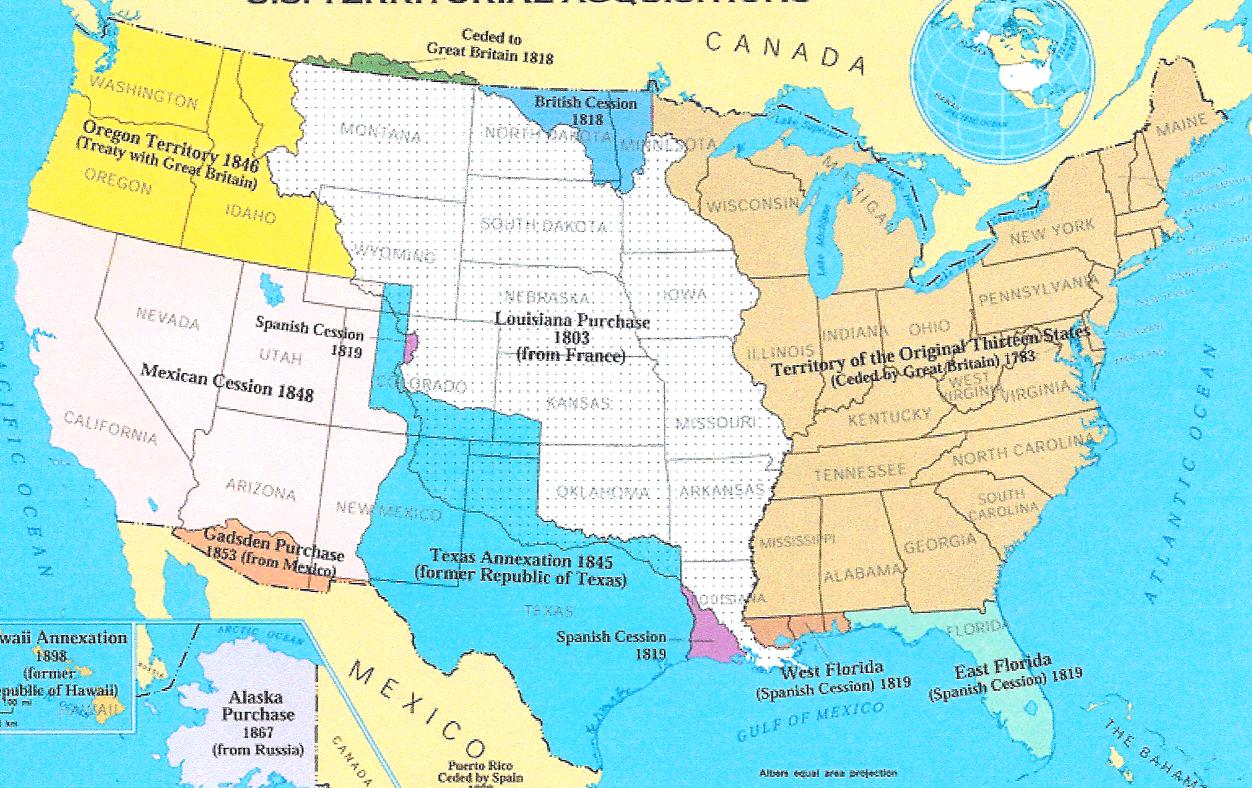

The Ware and Webb families were undergoing great changes the year Mary Ann was born, and so was the whole country. It was an exciting time for the United States. “For three cents an acre, (amounting to 15 million dollars) the United States purchased from France a huge region between the Mississippi and the Rockies.” (Wikipedia) It was known as the Louisiana Purchase, and it would forever change the face of America. The purchase, which doubled the size of the country, was a defining moment in the administration of Thomas Jefferson, who was president at the time. Kentucky, still a little rough around the edges herself, was now the “jumping off” point for further expansion west, luring a whole new generation of pioneers to explore new lands. For those like Mary Ann, born in the first part of the new century, it must have seemed like a whole new world.

Maps showing Louisiana Purchase

At the age of 17, Mary Ann Todd Webb married William Nicholson, of Cooper County, on October 19, 1820. (Ref. 192, 2009) Their first child was Webb (nicknamed John) Nicholson, followed by James Cuthbert, William P., and Mary Susan. This was only the beginning of what would be their large family.

On July 10, 1828, the couple provided Grandma Lucy with another namesake, Lucy C. Nicholson. “This granddaughter was destined to be known as the ‘Belle of Boonville’, Kentucky.” (Ref. 174, 2009) She was a very bright woman; accomplished in reading both Latin and French. She met and fell in love with Major David Herndon Lindsay, an army officer who had recently lost his wife. They were engaged to be married when the Civil War began, but because of the turmoil of the times, they decided to defer their wedding until after the hostilities ceased.

Lucy was earnestly devoted to the cause of the Confederacy. She helped establish a hospital for the wounded, and during the winter of 1862, she and other women in Springfield, Missouri, made clothing for the soldiers. However, upon hearing that the Confederate men fighting in the area were in dire need of certain medicines, she took her dedication to a whole new level.

Showing great creativity, Lucy used the fashion styles of the day to accomplish her mission in getting the desperately needed supplies to the southern army. It was very common for women to wear some kind of head gear when they were out in public, so she made a most unusual hat for herself. She took two immense rolls of velvet and rolled quinine in one and morphine in the other. Then “she put one around the coil of her hair and the other around the crown of her head.” (Ref. 2275) For good measure, she “put 22 pair of home-knit socks under the hoops of her skirt.” (Ref. 2275) She succeeded in her daring escapade, but someone, unthinkingly, spoke of her adventure and the news reached the Federal army. “On her return home to Boonville, in the spring of 1862, she was arrested as a

dangerous rebel and was placed in jail for smuggling medicines.” (Ref. 174, 793, 2009) She stayed confined to prison for eight weeks until Colonel Crittenden, from the Union army, arranged for her release. He commented that he was “not about the business of arresting women and children.”

Lucy then began teaching school, but her problems were far from over. The Union provost marshal in St. Louis, Colonel Dicks, apparently felt she “inspired sufficient terror so he called for her arrest by a force of 40 men. Colonels James Rollins, Odon Guitar, and others interested themselves to have the lady released. Colonel Dicks, however, had her taken to St. Louis and incarcerated in Gratiot Street Prison.” (Ref. 2009, 2275) It was a prison well known for holding not just Confederate soldiers, but spies, guerillas, and civilians suspected of disloyalty. It was, needless to say, not a good place to be, especially for a woman.

For several long weeks, Lucy survived the horrible conditions for which Gratiot was well known. She was then taken to another

prison in the city called Chestnut Street Prison, where she stayed for an additional two weeks.” (Ref. 2009, 2275)

![]() Prison record

Prison record

As was frequently the punishment in cases such as hers, “she was subsequently banished from St. Louis with a number of other ladies and sent south by steamer to Okolona, Mississippi.” (Ref. 2009, 2275)

Upon reaching Mississippi, the poor female travelers were left to their own devices without food or shelter of any kind. Lucy, with the wife of General Frost as a traveling companion, managed to journey all the way from Mississippi to Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where Major Lindsay was serving in the Confederate army under General Frost. Finally, “on the 22nd day of July 1863 at the General’s headquarters, Lucy and Major Lindsay were married. She remained with the army until the close of the war, devoting much of her time to the aid and comfort of the soldiers.” (Ref. 2009, 2275) Many years later, Lucy died in 1923 at the age of 95 when she was burned to death in a house fire. (Ref. 174, 793, 2009) Her younger sister, Lizzie, was living with her at the time, and they perished together.

Mary Ann Webb and William Nicholson had five more children after the birth of Lucy. Elizabeth C. (Lizzie) Nicholson, born in 1832, never married. As stated above, she died, at the age of 91, in the same house fire that killed her sister. The two girls were followed by Alice Peachey Nicholson, Louise W. Nicholson,

L. Gertrude Nicholson, and Isabelle Eugenia (called Eugenia or Belle) Nicholson. Unfortunately, with a total of 10 children in the Nicholson household, their grandparents, Lucy and Isaac Webb, would only live long enough to know about the first six.

~~~~~~~~~~

CHILDREN OF:

MARY ANN TODD WEBB and WILLIAM NICHOLSON

B. March 15, 1803 B.

D. D.

Mary Ann Todd Webb was the daughter of Isaac and Lucy Webb and the granddaughter of James and Caty Ware. She married William Nicholson on October 19, 1820. (Ref. 192)

(1) Webb (a.k.a. John) Nicholson Died May 25, 1886

(2) James Cuthbert Nicholson Born: Oct. 1825

(3) William P. Nicholson

(4) Mary Susan Nicholson

(5) Lucy C. Nicholson Born: July 10, 1828 Died: April 3, 1923

Married Maj. David Herndon Lindsay

(6) Elizabeth C. (Lizzie) Nicholson Born: June 25, 1832 Died April 3, 1923

Never married. She lived with her sister, Lucy Lindsay, in Missouri and died at the age of 91 in the same house fire that killed her sister.

(7) Alice Peachey Nicholson Died: August 27, 1836

According to the book, Kentucky Obituaries, 1787-1854 by Glenn Clift, “Alice Peachey (Nicholson), youngest daughter (at the time) of W.P. and Mary Nicholson, of Baltimore, Maryland died at the Lexington Kentucky residence of M. T. Scott on August 27, 1836.”

(Ref. 192)

(8) Louise W. Nicholson Born: 1857 Died:

(9) L. Gertrude Nicholson Born: 1859 Died:

(10) Isabelle Eugenia (called Eugenia or Belle) Nicholson Born: July 1862 Did not marry Died after April 1923

Isaac

and Lucy’s ninth child, John Thompson Webb,

was born on March 18, 1805.

By this time their little home was

overflowing with children: Kitty (14), Winny (12), James (10), Isaac

Jr. (8), Lucy (6), Cuthbert (4), and Mary Ann (2). Hayes Library

records state that John Thompson “received

1,000 acres of land on Paint Creek in Ohio from his father and

mother, Isaac and Lucy Ware Webb, deed dated January 21, 1831.”

(Ref. 174)

Paint Creek

Paint Creek

John moved later to Alabama and that is where he died.

The last child for Lucy and Isaac was Elizabeth (Betsey) Frances Webb, born on September 12, 1806. Lucy, age 33 at the birth of this child, was just five months pregnant when her beloved father passed away. Grandpa James never got to meet this grandchild.

Betsey first married Reverend Joseph P. Cunningham and they had four children before he passed away. Isaac Webb Cunningham (called Webb) was born in 1827, followed by Robert, Lucy, and Joseph, who was called John. In Lucy’s letter to her niece, Sally Stribling, she wrote, “Betsey Cunningham has two very interesting boys, Webb and Robert. She would have been so delighted to have met with you and Josiah.” (Ref. 597)

After Robert’s death, Betsey remarried

in July of 1836. Her husband, Mathew Thompson Scott (known as

Thompson), had been previously married to her older sister Winny (who

died in 1833).

There was quite a large difference in their

ages. In one letter President Hayes wrote to his sister, he

mentioned that “Aunt Betsey is twenty years

younger than her husband and the youngest woman of her age I have

ever seen.” (Ref.

174) Hayes described another visit with the

Scotts in a letter to his sister in 1855:

There was quite a large difference in their

ages. In one letter President Hayes wrote to his sister, he

mentioned that “Aunt Betsey is twenty years

younger than her husband and the youngest woman of her age I have

ever seen.” (Ref.

174) Hayes described another visit with the

Scotts in a letter to his sister in 1855:

“I . . . was soon at (the) home at Uncle Thompson Scott’s cousinly mansion at Lexington, Kentucky. The family here consists of Uncle Thompson, a fine, old gentlemen of over seventy years old, with faculties unimpaired; intelligent, and cheerful. He has been in the bank, of which he is president, some forty years, is staid and sober, but not severe or strict. He is now reading the Bible at the other end of the room. His first wife [Winny] and present wife [Betsy Webb Cunningham] were sisters of Lucy’s father [James Webb]. There is one unmarried daughter, Cousin Lucy, a fine good girl, getting passé, but good-looking; two sons, twenty and twenty-two, fair specimens of the better sort of Kentucky-bred young men.” (Ref. 174)

Cousin Lucy Cunningham must not have remained single much longer because, during his next visit, Hayes wrote that he “met Lucy Cunningham with her rich husband spending the honeymoon here after their tour.” He added, “The house is very large, rooms high, ventilation perfect, and nobody bothers or is bothered by anybody else. It is as independent as in a hotel and much the same in some things. Newcomers arrive constantly. The table ranging from ten to fifteen plates – plates, by the way, precisely like the blue old china ones Mother had in Delaware. . . . People here seem to live for the sake of living more than in most places.” (Ref.174)

Three years later, Mathew Thompson Scott died on

August 21, 1858, at the age of 72. According to records in Lexington, “He was a man of superior financial judgment and irreproachable integrity. (Ref. 976) He was certainly loved by his family. Lucy, who was twice his mother-in-law, wrote at one time that Mr. Scott “comes home in the evening; one of the best husbands living (and fathers).” (Ref. 597 Lucy went on to express her gratitude for her entire family when she wrote, “I often think, ‘who am I’ that God should be so kind to me in giving me such affectionate children and such kind husbands and wives to them all . . . for which I hope ever to be truly and humbly thankful.” (Ref. 597)

Grave

of Mathew T. Scott

Grave

of Mathew T. Scott

Photo taken by James and Judy Ware 2010

Scott section in the Lexington Cemetery

Photos courtesy of James & Judy Ware 2010

Scott family burial section in the Lexington Cemetery

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

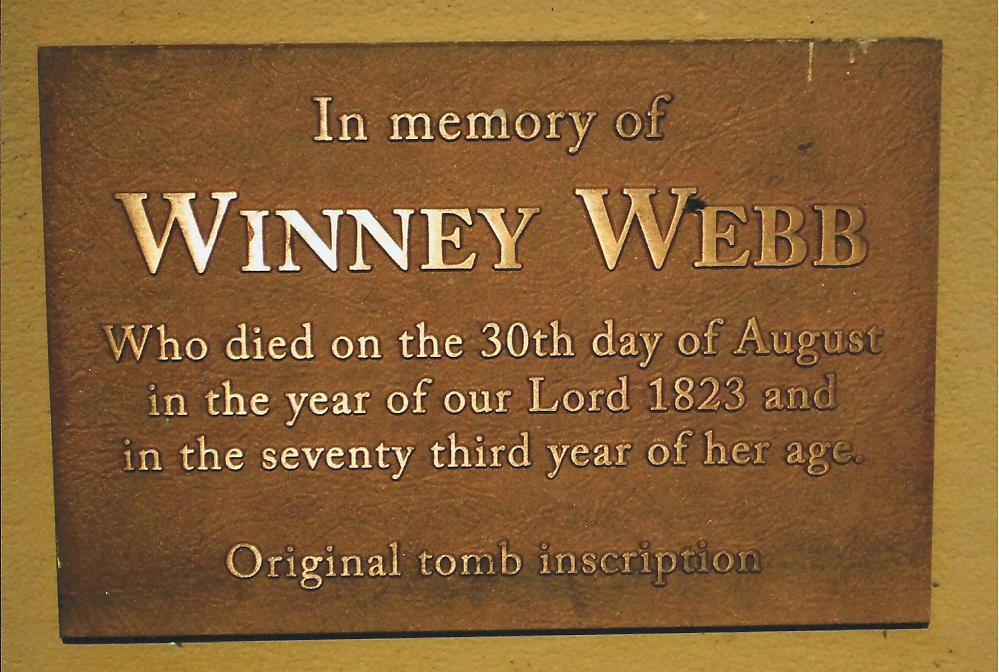

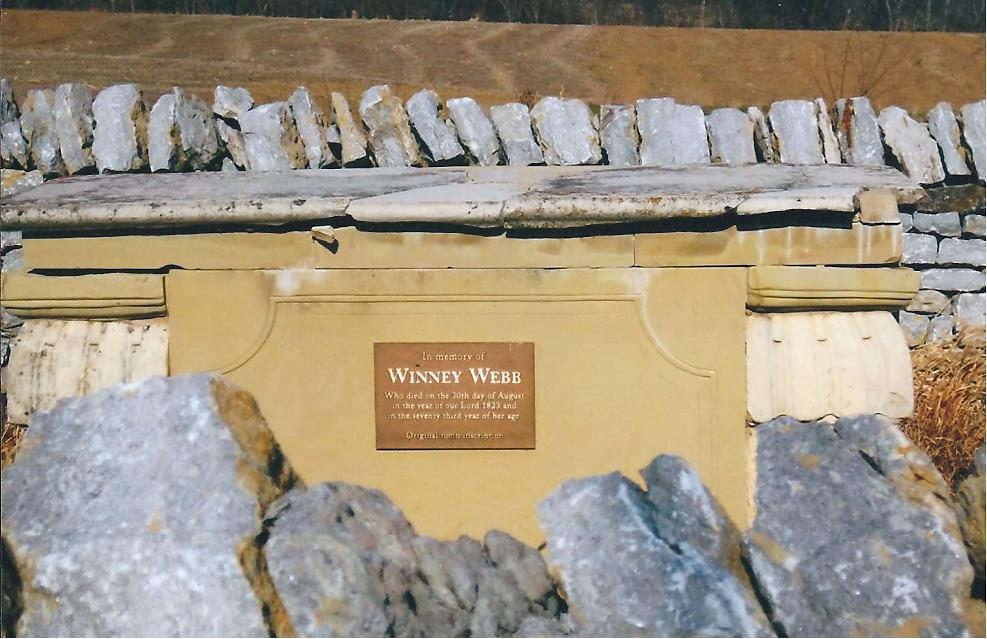

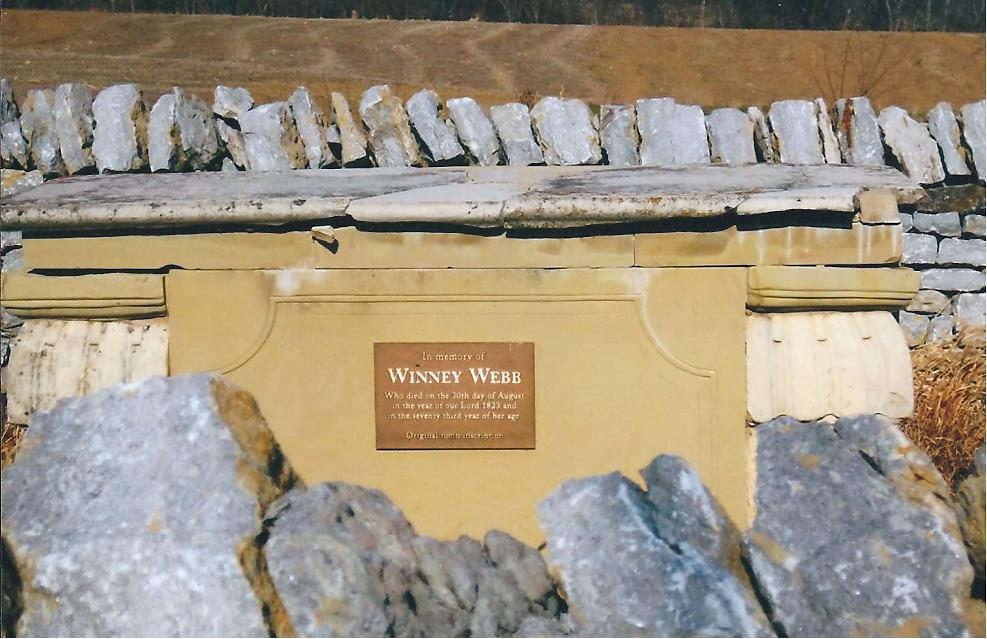

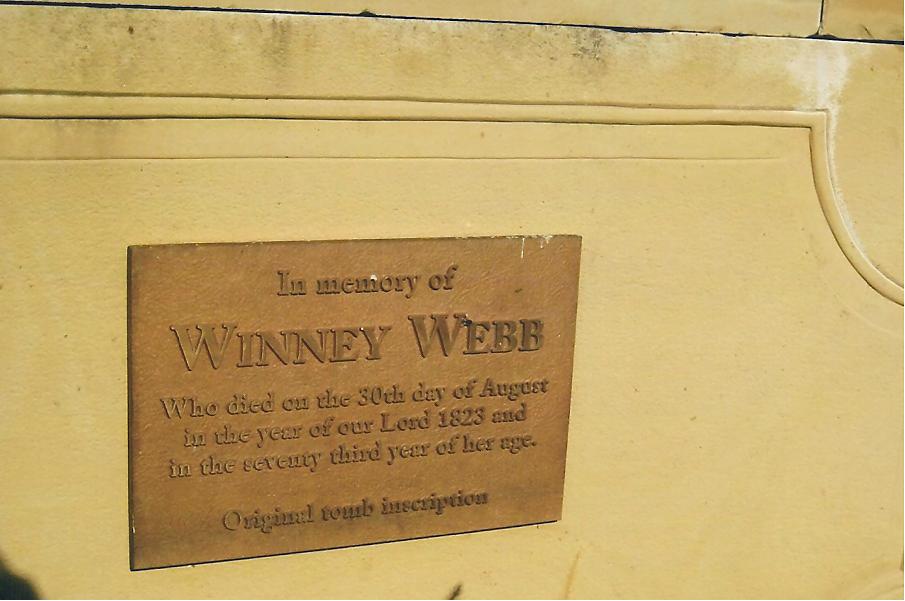

When the Webb brothers, Charles and Isaac, moved with their families from Virginia to Kentucky, they were accompanied by one of their sisters, Winney Webb. Winney was an extremely wealthy

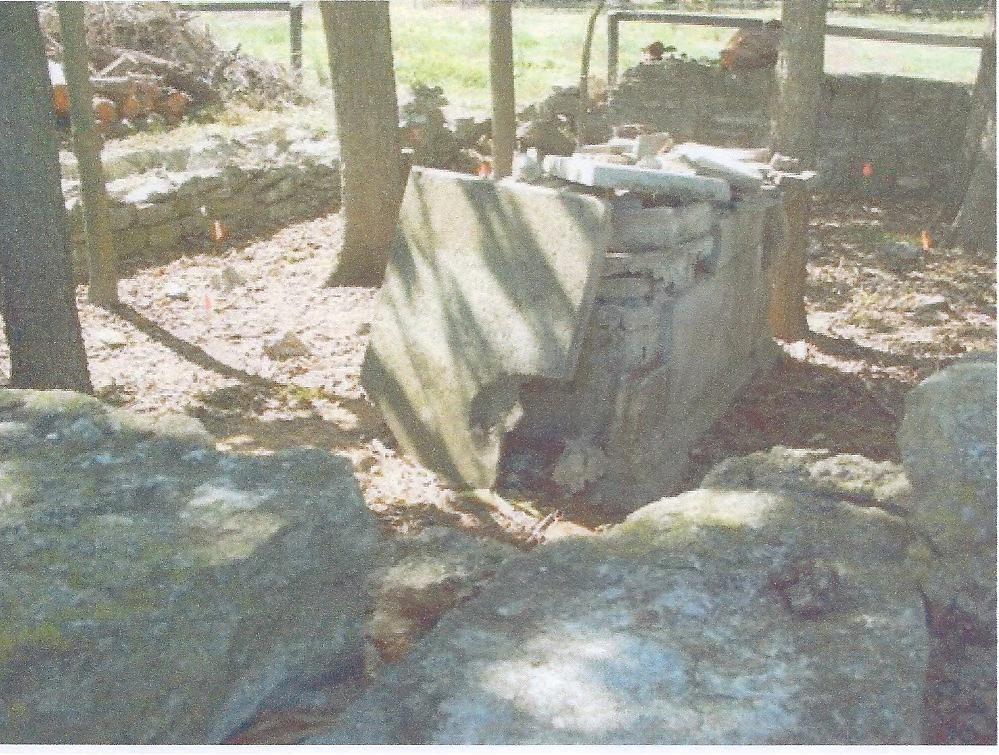

Tomb of Winney Webb-

Tomb of Winney Webb-

photo taken by James and Judy Ware 2010

woman who never married. As one historian stated, “At her death in 1823, Winney Webb, a spinster, had amassed an estate; composed of land, slaves, and personal property that would have been the envy of any of her male contemporaries, to whom she had loaned money on many occasions.” (Ref. 936, 2283) She was also a very generous woman, leaving her great wealth to her many nieces and nephews. (Ref. 452) The following is a list of the slaves she owned and bequeathed in her will:

To her brother, Isaac Webb:

(1) Rawley (blacksmith) (3) David (the cooper)

(2) Jerry (4) Turner

To nephew, James Webb:

(1) George (2) Clarissa (3) David (4) Phylis (5) Sam

(6) Cynthia (7) Alexander (8) Aggy (9) John

To nephew, Isaac Webb:

(1) Adam (2) Hannah and children, (3) George and (4) Sam

To nephew, Cuthbert Webb:

(1) Lucy (3) Henry

(2) Noble (4) Augustus

To nephew, John Webb:

(1) Nancy (3) Alfred

(2) Milton (4) Sam

To niece, Winny Scott:

(1) Sam (2) Adela (3) Julian

(4) John (5) Joanna (6) Winney (7) Isaac

To niece, Lucy Scott:

(1) Rachel

To niece, Mary Nicholson

(1) Amanda (2) Hampton

To niece, Elizabeth Webb:

(1) Mill (2) Tammy (3) Mariah

To nephew, Charles Webb:

(1) Lucy (2) Winny (3) George (eldest of the name)

To nephew, John Webb, from brother Charles:

(1) Rueben

To niece, Winny Webb:

(1) Lucy (2) Adam

To nephew, George Harrison:

(1) Harrison (2) Minerva (3) Mary

To nephew, John Bull:

(1) Phoebe

To niece, Frances Faunleroy:

(1) Sydney (2) Churchill (3) Eliza

To Thomas Conn, son of niece, Kitty Conn

(1) Anarchy

To other nieces

(1) Nancy (2) Molly (Ref. 452)

She made sure to make the following notation:

“It is my wish that my Negro, Rawley, who is now learning the shoemaker trade be free at 25 years of age. Also Mortimer and Sam be free at the same age. I also leave old Lucy free to be supported by Isaac Webb should she not be able to support herself.” (Ref. 452)

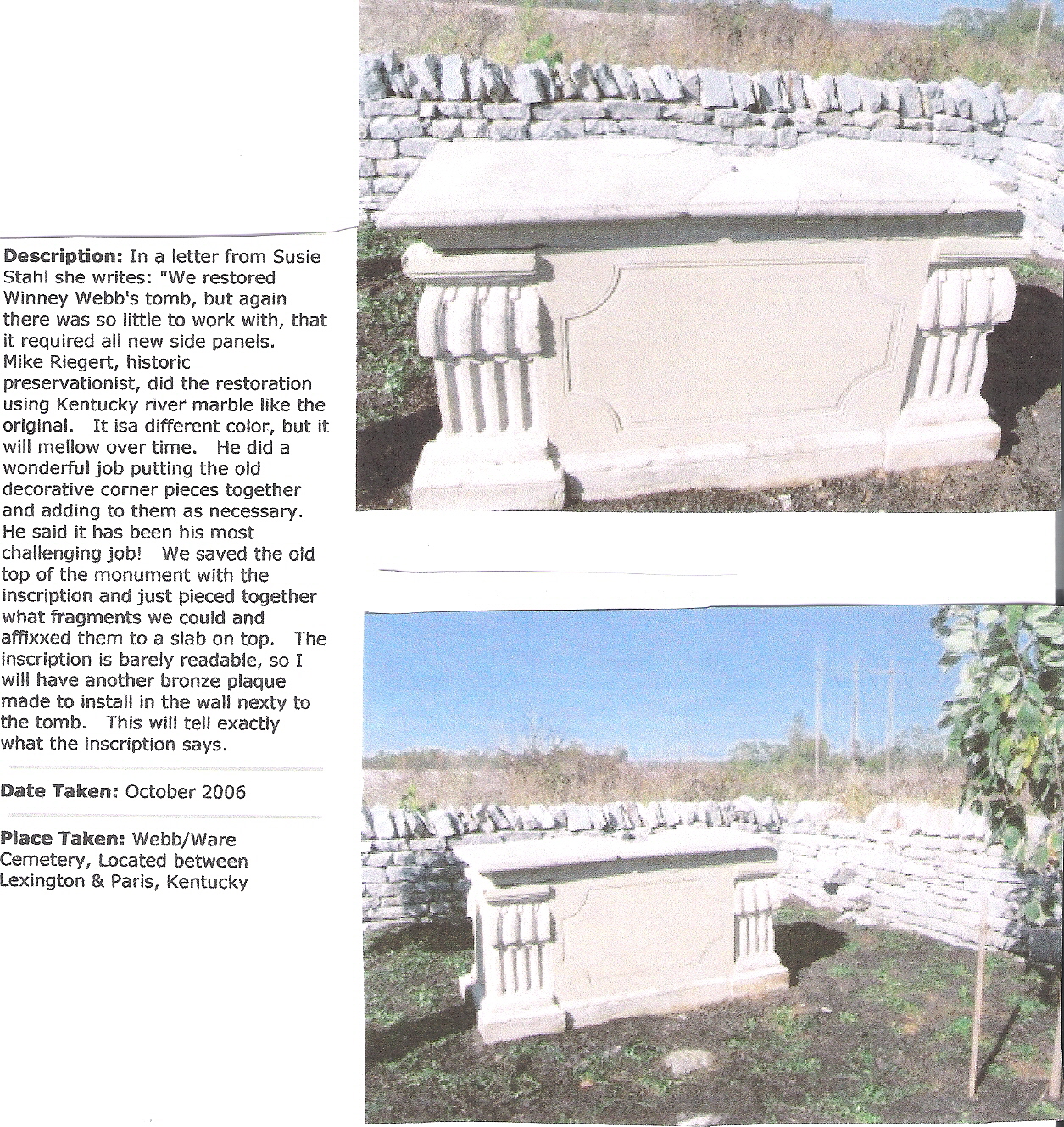

Winney seems to have been greatly admired by one and all, with many children being named after her. One descendant wrote, “Winney Webb, an extraordinary woman, was buried under this sumptuous box crypt, which she directed in her will to be erected over her grave. This beautifully restored grave is located on Stewart Road.” (Ref. 936) The following photos were taken by Susie Stahl who was part of an incredible restoration project concerning the Webb/Ware Cemetery in Kentucky.

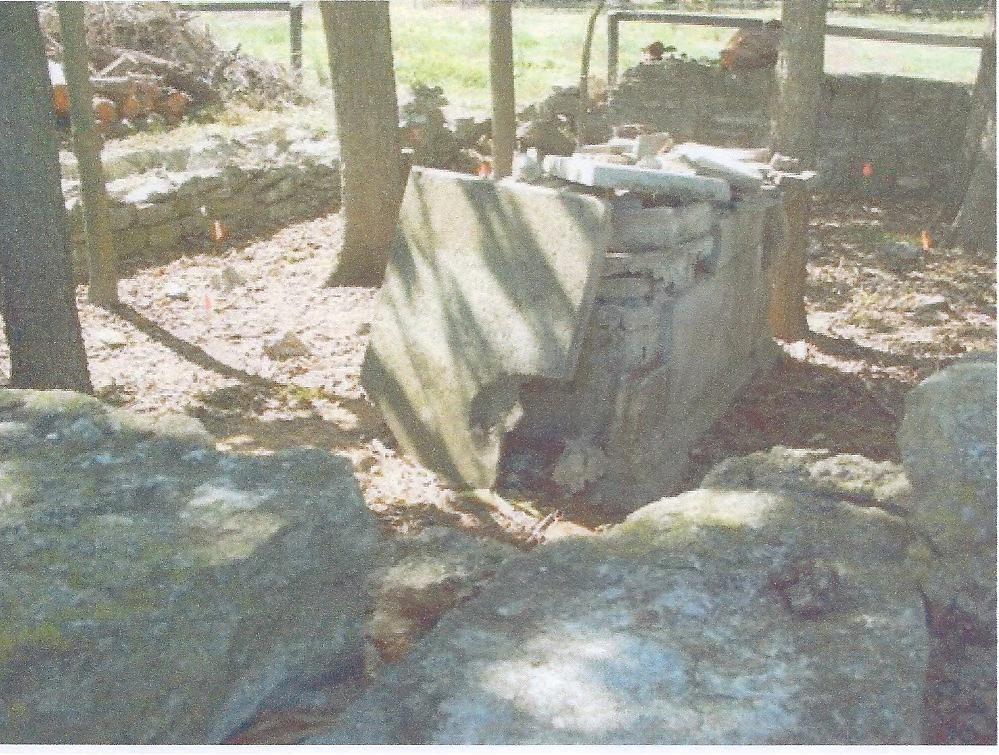

Winney Webb’s tomb

prior to

the restoration

Winney Webb’s tomb

prior to

the restoration

Winney’s tomb after restoration

Photos and explanations provided through the kindness of Susie Stahl and John Woods

Life in Kentucky was full and eventful for Lucy and Isaac. During the years they were raising their family, the world around them was undergoing some dramatic changes. Having watched the colonies unite into one, cohesive country, they would hear the news of President John Adams moving into the newly built White House and also hear of the burning of that very same house in the War of 1812. The year their last son was born, 1805, Lewis and Clark first laid eyes on the great Rocky Mountains and also reached the Pacific Ocean. Because of this, every day seemed to open up new horizons.

The Webb and Ware families enjoyed many years of

peaceful tranquility and prosperity. Lucy mentioned in one of her

letters that her daughter, Lucy Caroline, “is

so pleased with raising so many fowls, she and Winny (both). I was

up there two weeks ago, and I never saw the like of the fowls in my

life. I believe we had 150 turkeys and as many ducks and chickens.

I was all but distracted with the noise and fuss with feeding. When

I came home, I found a calm both in the house and yard; but for fowls

and children.”

(Ref.25)

Lucy’s letters to her relatives in Virginia provided a constant link between the close knit families. Her nephew, Josiah Ware, once wrote that “Aunt Lucy and my father were each other’s favorites, as she told me, but she must have been every one’s favorite that knew her. In every respect she was the most perfect woman I ever knew. She was old and white-headed when I first saw her.” (Ref. 299)

Josiah further wrote, “I knew Lucy Ware intimately and corresponded with her. When she was about 60 or 70 years old, her hair was cut short and was as white as snow. She was a perfect specimen of hospitality. She was rather fleshy, not too much so and about the height of Lucy (Webb) Hayes.” (Ref. 638) Josiah also described his Uncle Isaac as “a very small man, of an active figure. I first saw them at their house near Lexington, Kentucky about 1825.” (Ref. 289,638)

When Josiah visited with President and Mrs. Hayes at the White House, he always enjoyed the opportunity to lovingly reminisce about his family ties in Kentucky. He was able to provide personal information on so many of Lucy Hayes’ family that had died before she had a chance to really know them. She must have been very grateful for that. At one time, Josiah mentioned all the letters that he and Lucy’s grandmother, Lucy Webb, had exchanged over the years, saying, “I had a large bundle of them; our correspondence was regular and her sheet always full and as if it flowed from her heart.” (Ref. 299)

Those happy times for Lucy and Isaac came to an abrupt end in 1833, when cholera settled like a blanket of death over Kentucky. As author, George W. Ranck, described it:

“The streets were silent and deserted by everything but horses and dead-carts, and to complete the desperate condition of things three physicians died, three more were absent, and of the rest scarcely one escaped an attack of the disease. The clergy, active as they were, could not meet one-third of the demands made upon them.” Businesses closed and “men passed their most intimate friends in silence and afar off, staring like lunatics, for fear the contagion was upon them. The dead could not be buried fast enough, nor could coffins be had to meet half the demand . . . many of the dead were buried in trunks, boxes, or simply wrapped in the bedclothes upon which they had just expired, placed in carts, and hurried off for burial without a prayer being said and no attendant but the driver. The grave yards were choked . . . out of one family of nineteen people, seventeen died. By July, cholera had killed over five hundred persons, and the whole city was in mourning. The terrors and sufferings in Lexington during the fearful cholera season of ‘33’ no pen can describe.” (Ref. 2256)

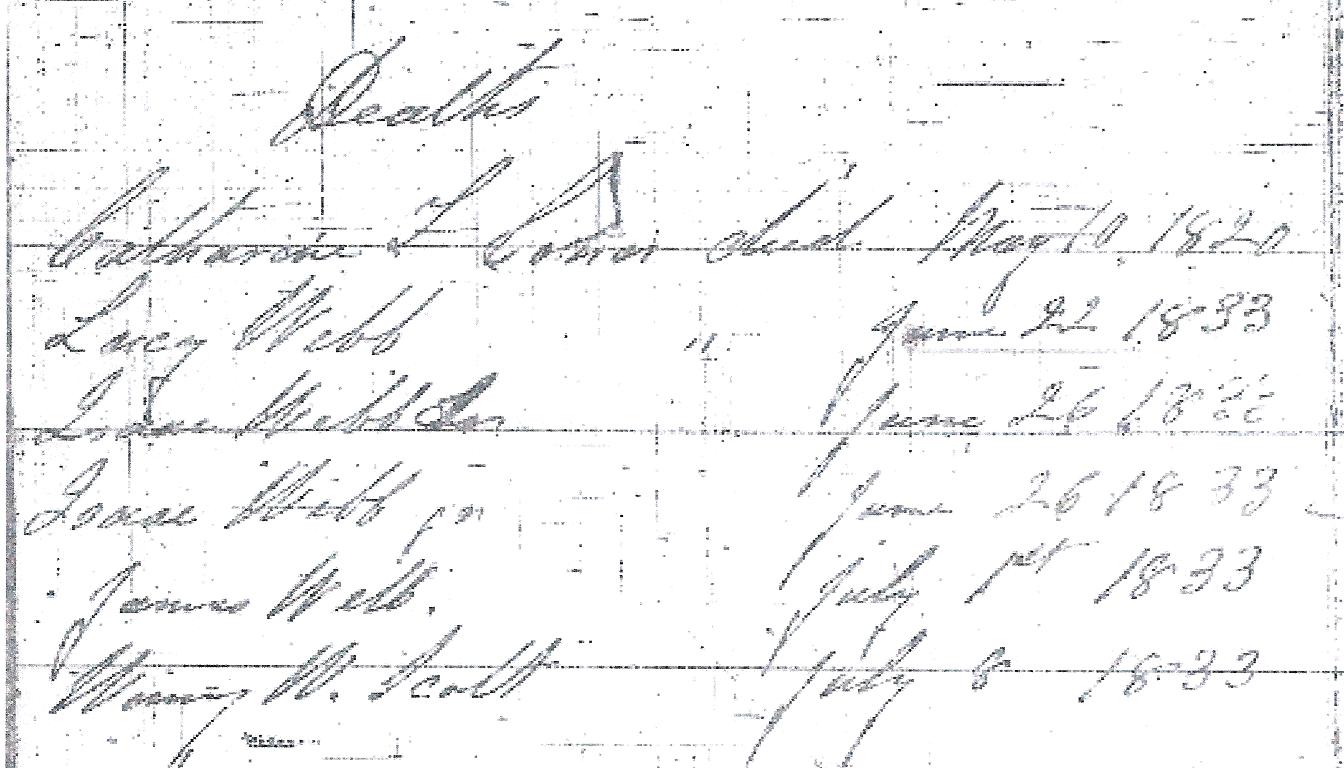

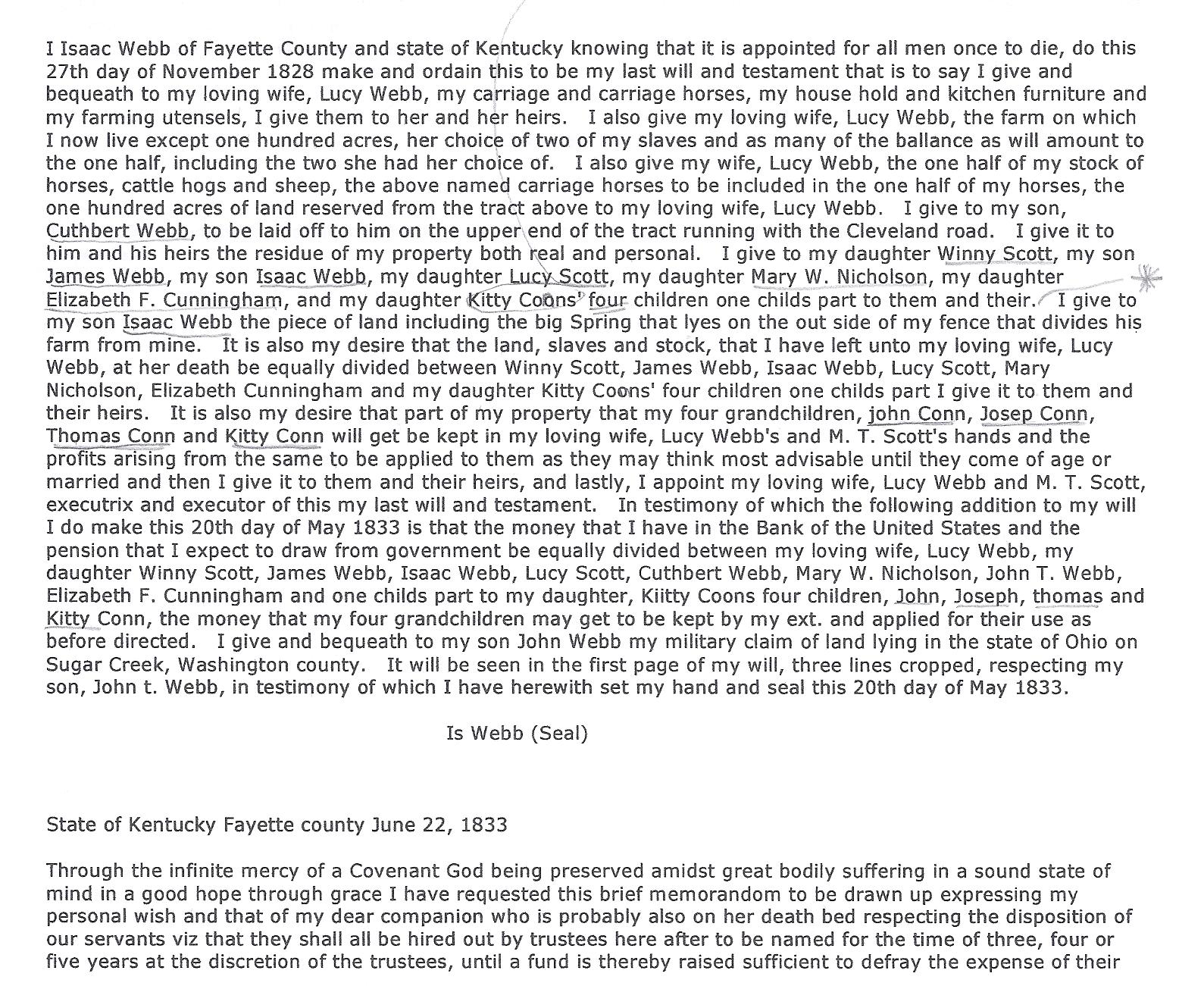

It was, indeed, a year of grieving. As mentioned previously, many of the children and grandchildren of Lucy and Isaac succumbed to the disease in a short span of time. On June 22, 1833, “Isaac added a section to his will (he knew he was on his death bed and knew Lucy was too) pertaining to the disposition of his slaves and the wish that they be hired out for 3-5 years until a fund was raised sufficient to defray the expense of their removal to Liberia and comfortable settlement there. If any slave should refuse to be moved, they must remain in bondage.” (Ref. 296 )

In a letter written from Isaac Scott to President Hayes in 1883, Isaac sought to explain more fully the circumstances surrounding the deaths of the some of the family members during that time.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

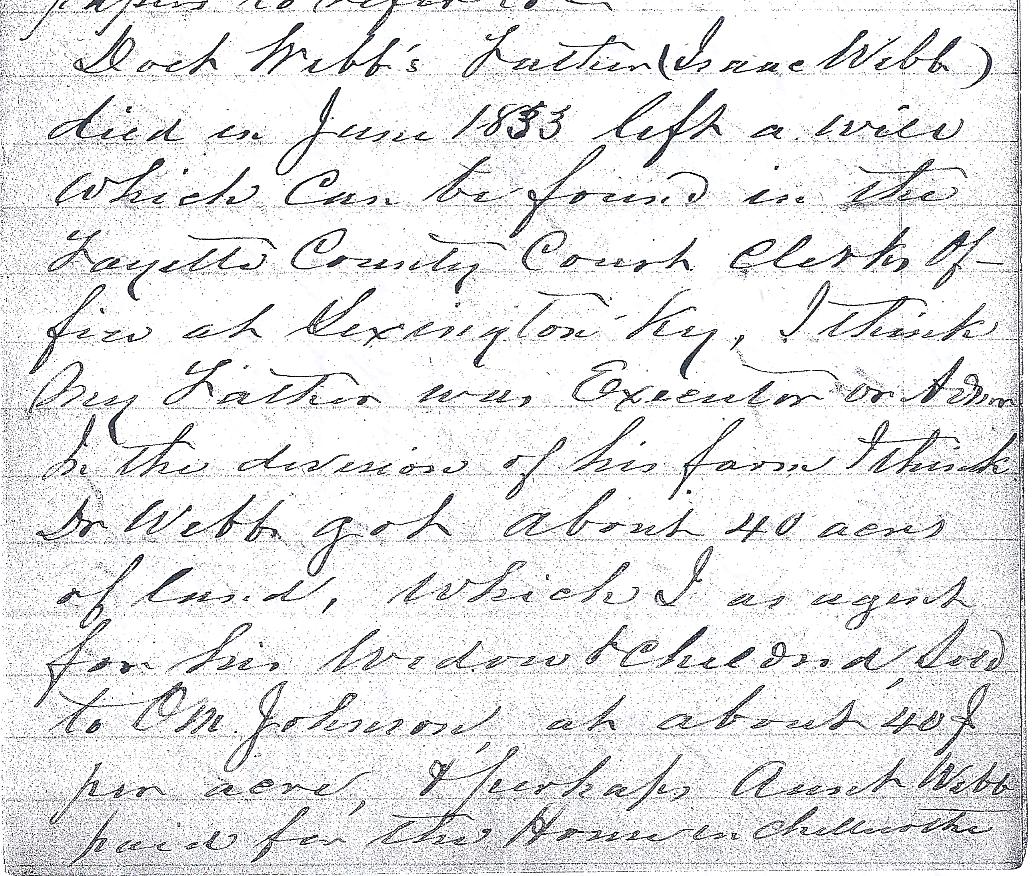

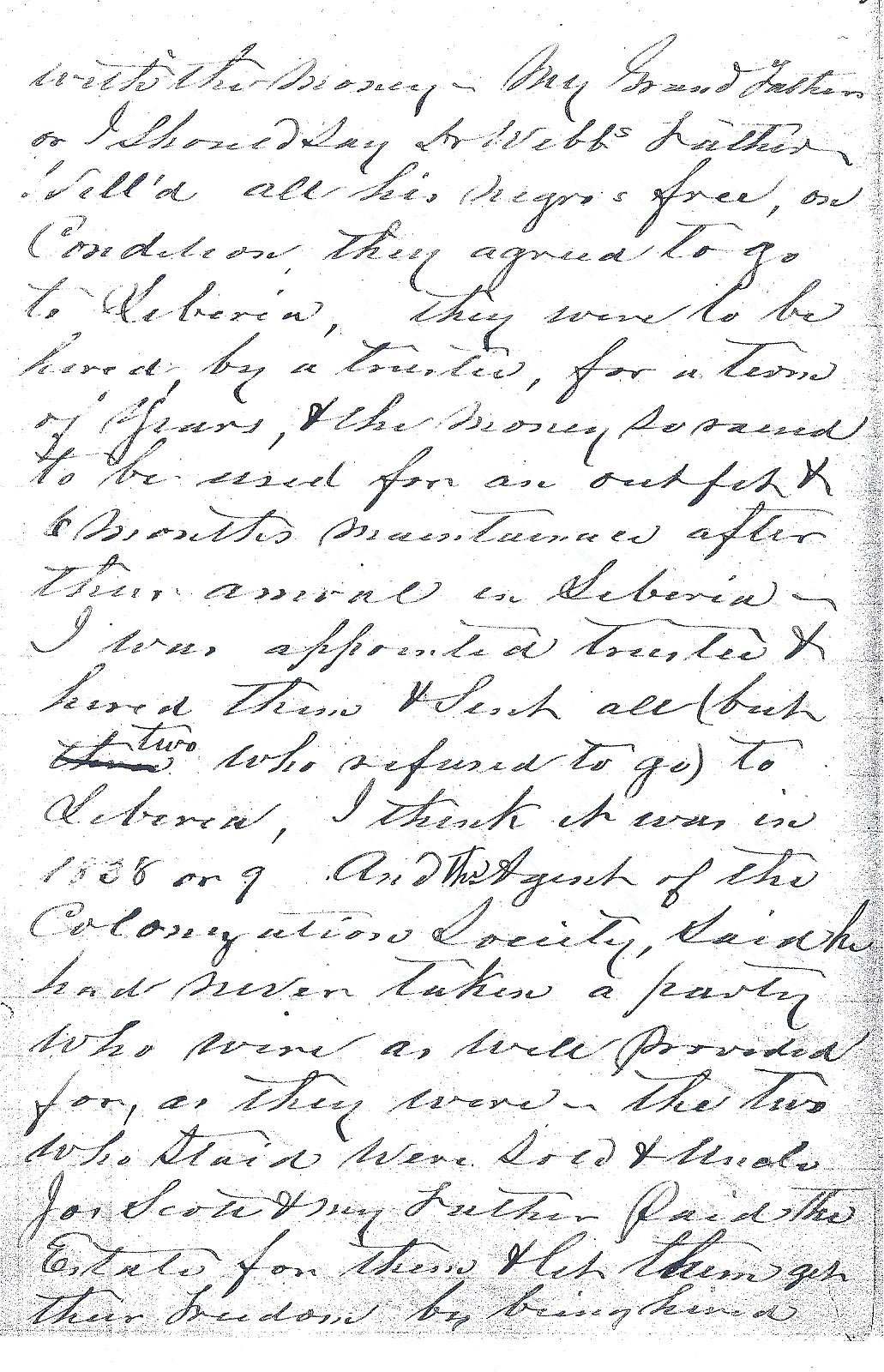

“Doctor Webb’s father [Isaac Webb] died in June 1833 - left a will which can be found in the Fayette County Court Clerk’s office at Lexington, Kentucky, I think. My father [Mathew Thompson Scott] was Executor or Administer in the division of his farm, I think. Dr. Webb got about 40 acres of land, which I, as agent for his widow and children, sold to – Johnson, at about $40.00 per acre, and perhaps Aunt Webb paid for the house in Chillicothe with the money. My grandfather, or I should say, Dr. Webb’s father [Isaac Webb] willed all his Negroes free on condition they agreed to go to Liberia. They were to be hired by a trustee for a term of years and the money so raised to be used for an outfit and 6 months maintenance after their arrival in Liberia. I was appointed trustee and hired them and sent all (but two who refused to go) to Liberia. I think it was in 1838 or 9. And the agent of the Colonization Society said he had never taken a party who were as well provided for as they were. The two who staid [stayed] were sold and Uncle Joseph Scott and my father paid the estate for them and let them get their freedom by being hired out until their hire paid the amount they were valued at. When I was in Lexington in 1871, I saw one of them; the other has been dead many years.” (Ref. 296, 300)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sections of the letter written to Hayes in 1883 – entire original letter owned by James & Judy Ware

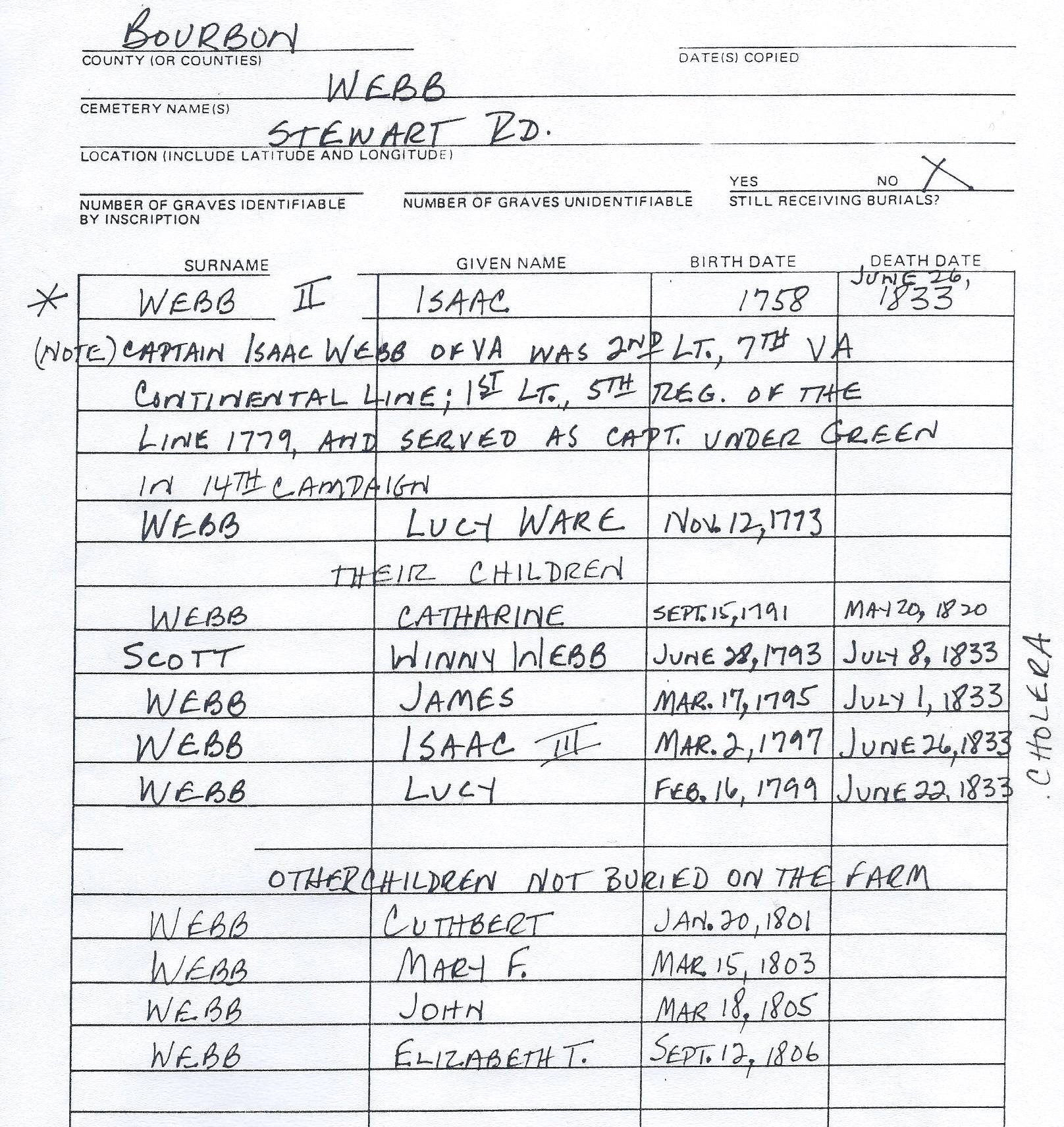

Most of the family members were buried in a small cemetery near the home of Isaac Webb. One source locates the graveyard as “on Stewart Road.” (Ref. 934) In 1998, another researcher provided more detailed instructions on how to find the cemetery. “I have three ‘sources’ that locate the property in Fayette County, about two miles on the Houston Road from its intersection with Briar Hill Pike in Fayette County. For whatever use it is, that road runs northwesterly to and along a Houston Creek on to where it meets the Lexington-Paris Pike (the Antioch Church is at the Lexington-Paris Pike juncture, in Bourbon County, where it is known as the Antioch Pike.) The road markers in Fayette County now show that road as the Huston-Antioch Road and a current map shows the name as Antioch Road (most of it is in Bourbon County.) My sources say a family burial ground is about two miles along the Houston Road, near Isaac Webb’s house. The Department of Transportation has a topographic map where a spot is accompanied by the letter ‘CEM’ (which I was told means “cemetery”). It seems a bit less than two miles down (or up) that road, in Bourbon County but near the Fayette line. A private drive or trail appears on the map where the property shows on that map, but I was unable to pick it out on the 1974 aerial photo.” (Ref. 944) It was not an easy site to find because it was on private property then and now, making access to it difficult.

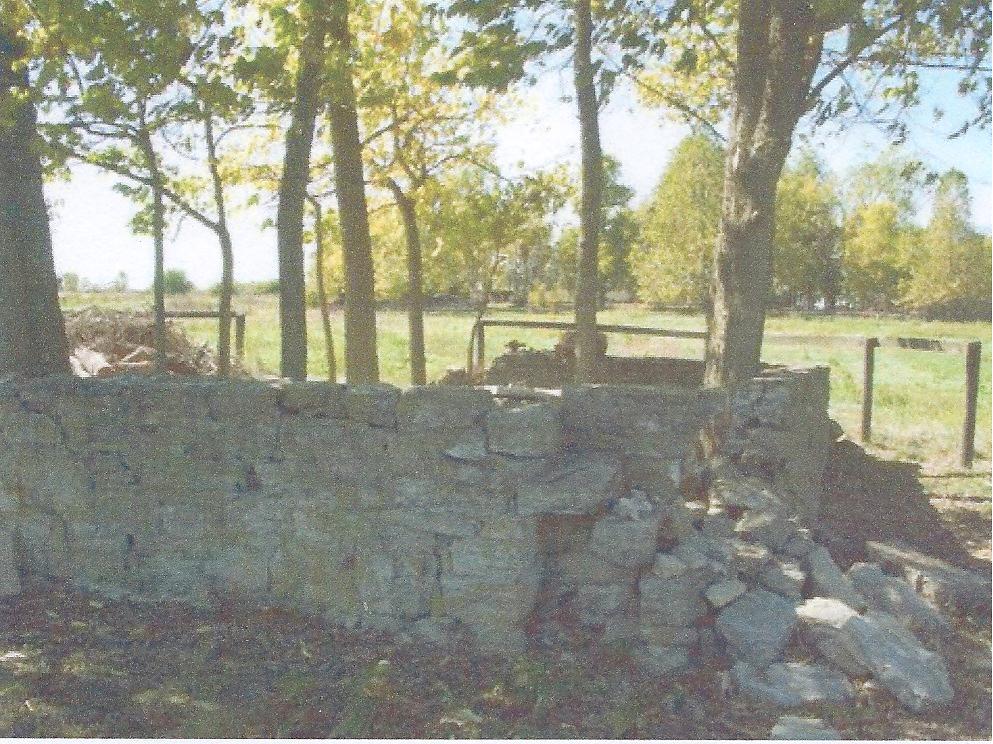

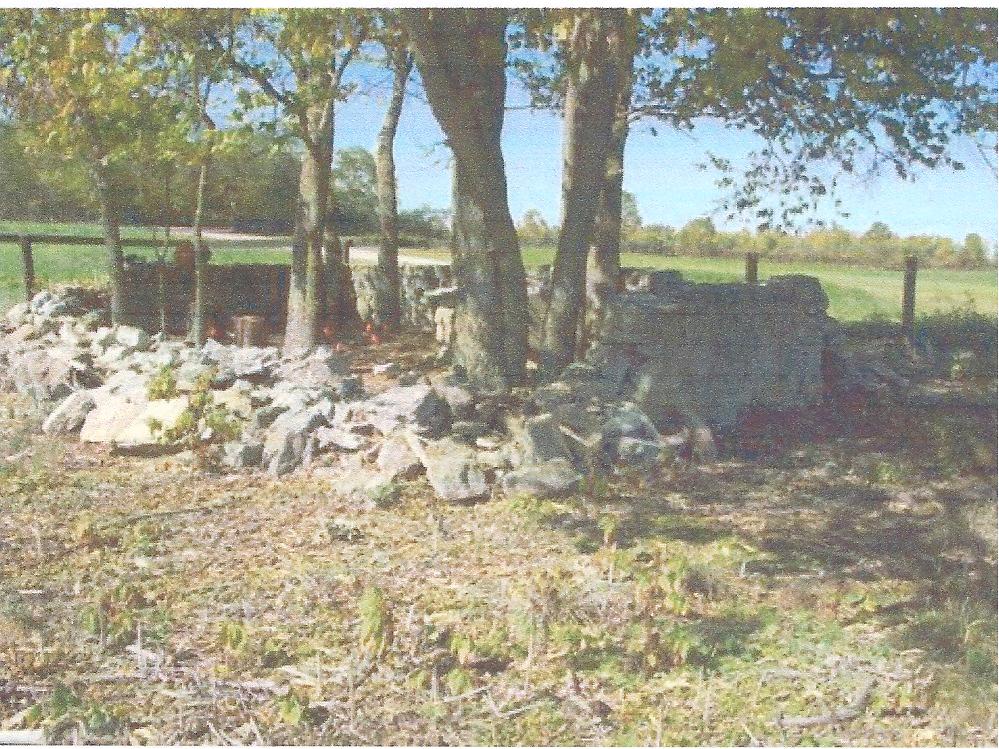

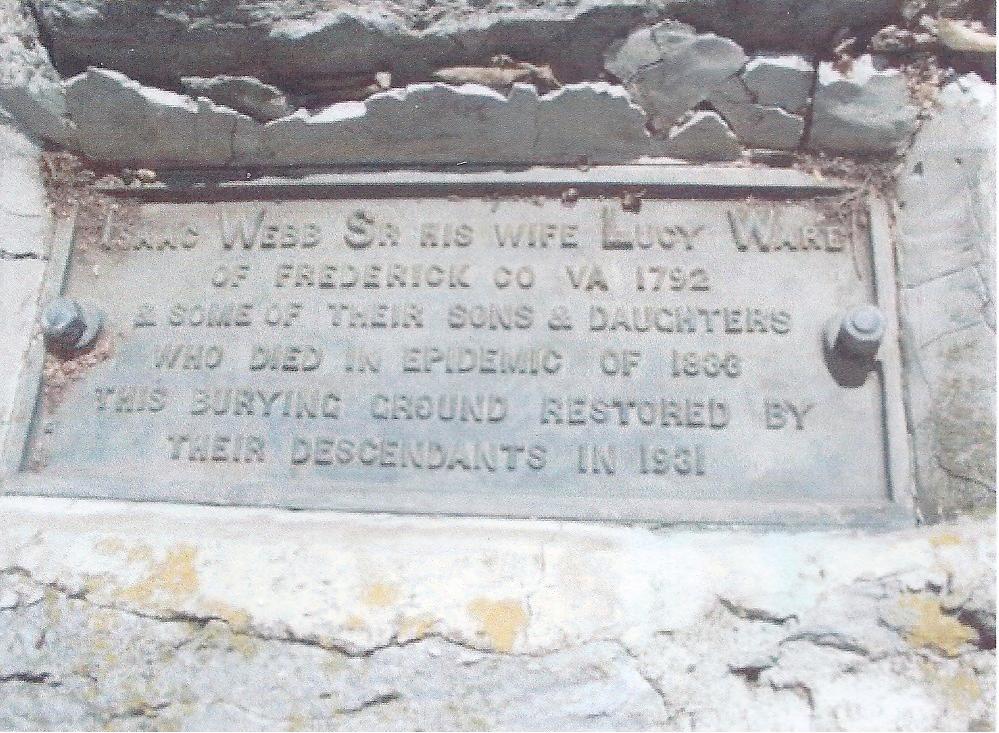

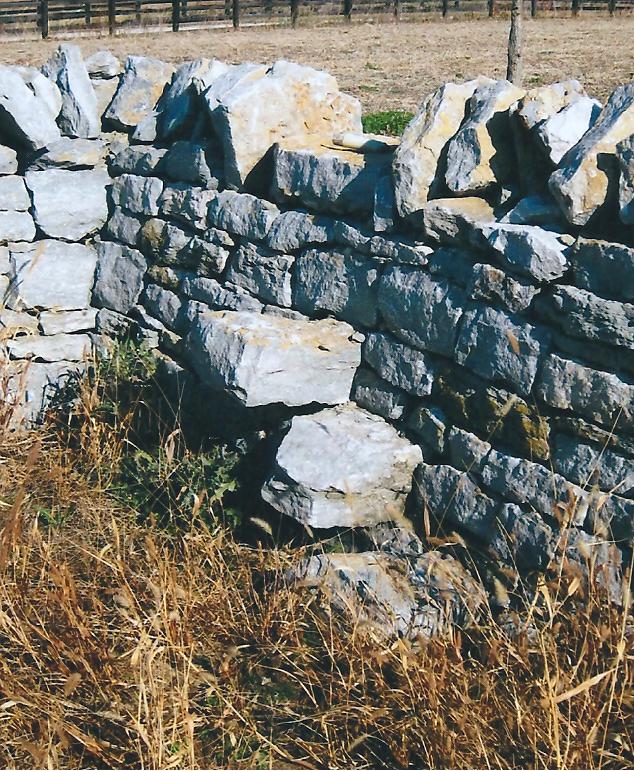

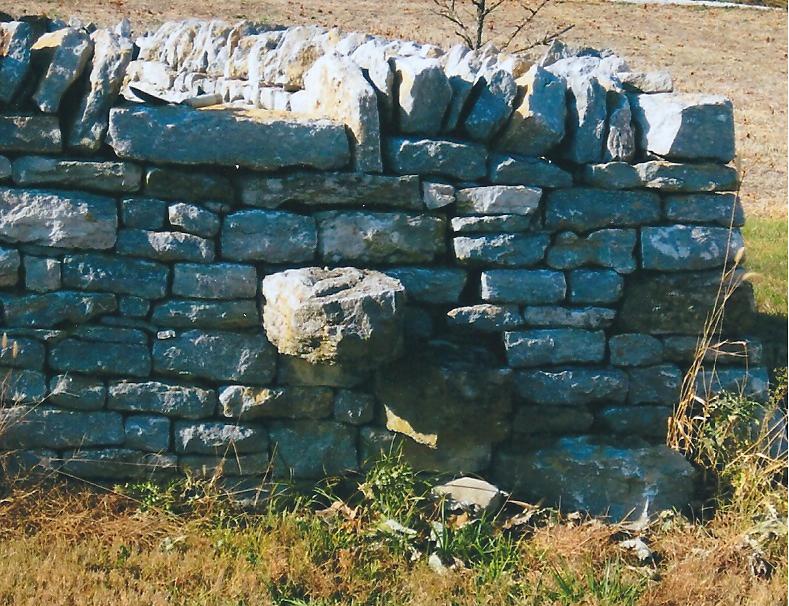

In 1931, Ware and Webb family descendants located and restored the old cemetery. They enclosed it with a 20 foot by 30 foot stone wall which was about four feet high and cemented. They even placed a plaque commemorating the site: “Years took its toll, however, and the family resting place again fell into sad disrepair. The large tombstone of Isaac’s sister (Winny Webb) had all but broken apart and the surrounding wall and other graves were hardly recognizable.” (Ref. 2095)

The following are photos of the site just prior to the new millennium:

Photos of the Webb/Ware

Cemetery before current restoration

Photos of the Webb/Ware

Cemetery before current restoration

Webb/Ware Cemetery prior to the most recent

restoration

Old Webb/Ware Family Cemetery before restoration

Winney’s

old marker

Winney’s

old marker

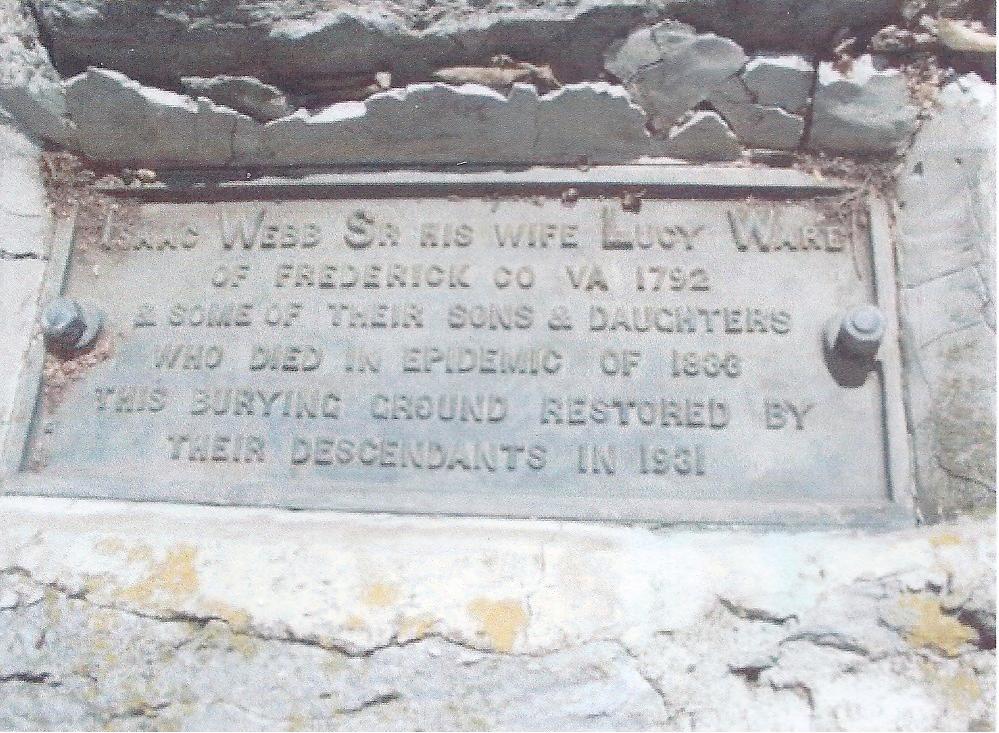

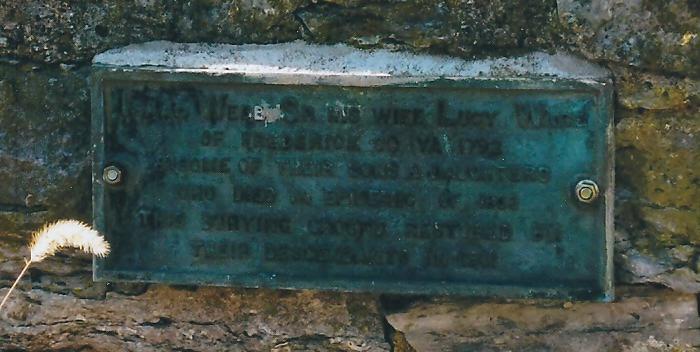

INSCRIPTION

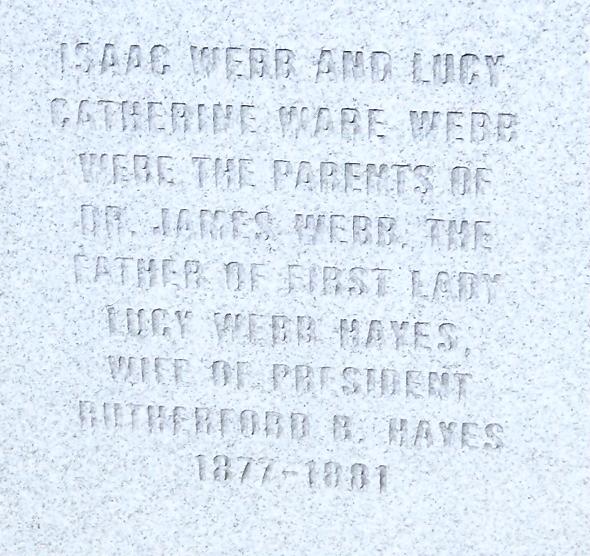

“Isaac Webb Sr. his wife Lucy Ware

of Frederick County Virginia 1792

and some of their sons and daughters

who died in epidemic of 1833. This burying

ground restored by their descendants in 1931.” (Ref. 417)

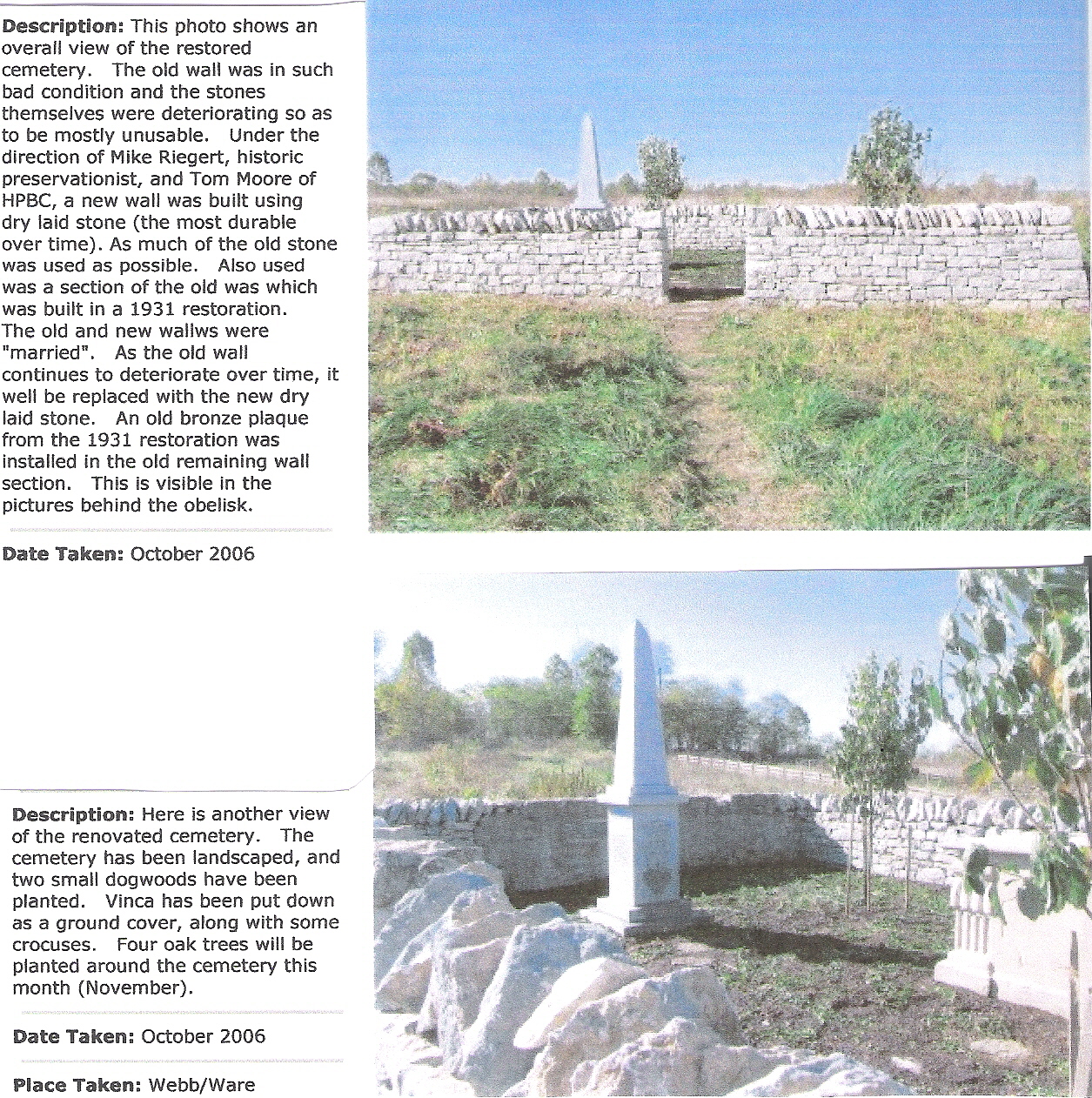

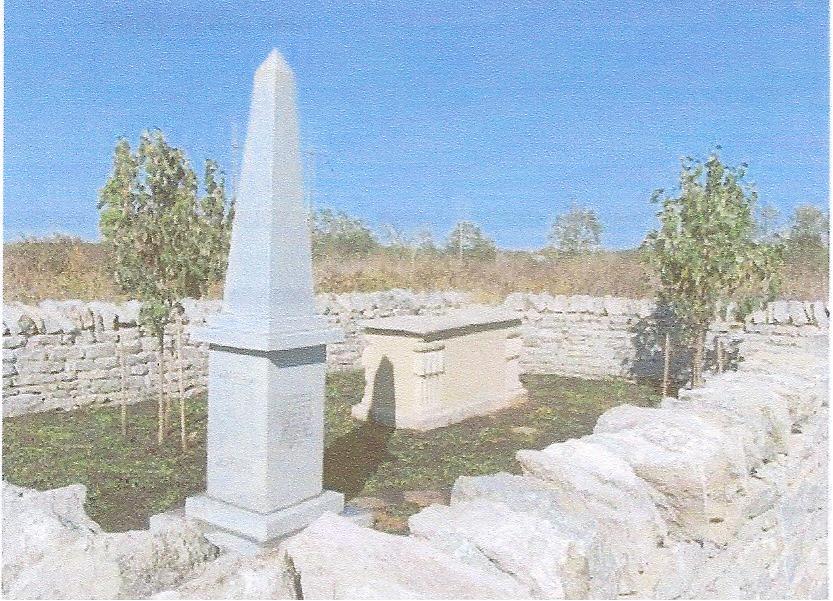

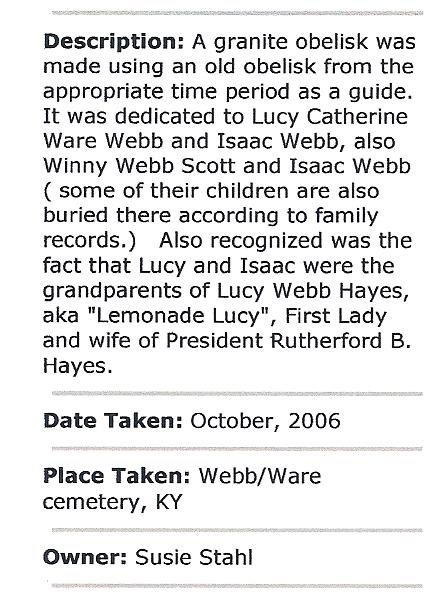

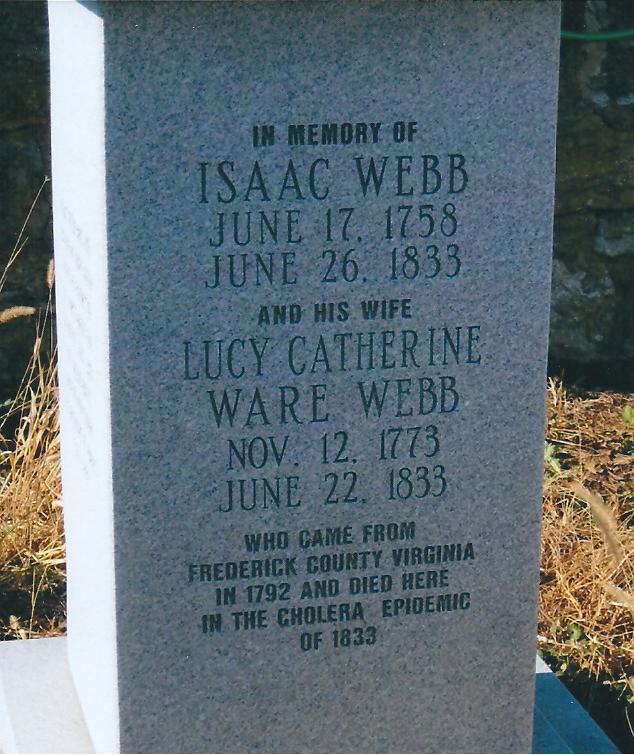

In 2006, this wonderful, old cemetery got another facelift from some very caring family members. The amount of time, money, and love that went into its restoration is a testimony to the kind hearts of those involved. Mike Riegert and Tom Moore of the Historic Paris Bourbon County/Hopewell Museum were the historical preservationists on the project, and Susie Stahl did an incredible job of overseeing everything and keeping it well documented. What a remarkable job was done!! One of the pivotal supporters of this project, John Woods, died suddenly a few years ago, but his enthusiastic backing on this restoration will be forever appreciated by many generations to come.

Webb/Ware

Cemetery after restoration in 2006

Thankfully, people have carefully recorded the information inscribed on the old tombstones so these facts about Lucy and Isaac have not been lost to weather and time.

Document on file at the Kentucky State Historical Library

(Ref. 2283)

In 2010, James and Judy Ware, from Oklahoma, finally found the old cemetery during a research trip to Kentucky. With the kind help of Tom Moore, the site was located and current pictures taken at the time. It was interesting to see how much change had occurred in the few short years since the restoration of 2006. The following photographs were all taken during that visit.

Located across a large field

Property owner’s home & barn is

Property owner’s home & barn is

in the background

Entry road leading to the Webb/Ware Cemetery

Looking back toward the road

P

Webb/Ware Cemetery 2010

Inside the bricked in area

Inside the bricked in area

Entering

by the gate

Entering

by the gate

Sadly, it was very overgrown inside the walled area

Photos taken 2010

There is writing on each side of the tall monument

Grave

of Winney Webb

Grave

of Winney Webb

(spinster sister of Isaac & Charles Webb)

When they did the restoration in 2006, they were very careful to keep as much of the original cemetery pieces as possible. The old marker that was placed in the first restoration of 1931 was still embedded in the walls in 2010.

2006

2006

2010

2010