There were many women in Ware ancestry who contributed to the common good, but none as much as Elizabeth Parsons Ware; to some of the rights we women, enjoy today.

When the Constitution was written, it was based on the values of the time; men’s values and liberties. Women were considered as so much property, equal to slaves. Children had even less status. When a young woman came into marriage, she might have possessed her clothing, a few personal items and possibly a dowry or land. These became the property of her husband. And if she were to leave the marriage, she would leave with nothing.

Legally the only way a man could divorce in many states, was to declare his wife insane. Sometimes women were “put away” for just being contrary to their husband or his beliefs, alcoholism, depression or menopause. Women were declared lunatic before some legal official, and were sent away to an asylum, often never to see their children or families again. The husband had total control over her incarceration, fore-biding her access to other family members. There she wasted away her days until she finally went insane or someone intervened on her behalf.

Doctors were not equipped at the time to deal with mental illness and so asylums were built to house them. Often they were part of the prison system, to help cut back on the costs of food and care. Sometimes the better tempered women were lent out to work at local farms for a low wage. All in all the asylums were vial places with inadequate food and comforts. Sanitary conditions were not stressed and a patient might die of disease.

“The patients were never washed all over, although they were the lowest, filthiest class of prisoners. They could not wait upon themselves anymore than an infant, in many instances, and none took the trouble to wait on them. The accumulation of this defilement about their persons, their beds, their rooms, and the unfragrant puddles of water through which they which they would delight to wade and wallow, rendered the exhalations in every part of the hall almost intolerable.” (1)

“Treatments” and punishments of all manner were inflicted upon the women. “A little ale occasionally is the principal part of the medical treatment which these patients receive, unless his medical treatment consists in ‘laying on of hands,’ for this treatment is almost universally bestowed. But the manner in which this was practiced, varied very much in different cases.” (1)

“One night I was aroused from my slumbers by the screams of a new patient who was entered in my hall. The welcome she received from her keepers, Miss Smith and Miss Bailey, so frightened her that she supposed they were going to kill her.

Therefore, for screaming under these circumstances, they forced her into a screen-room and locked her up. Still fearing the worst, she continued to call for ‘Help!’ Instead of attempting to soothe and quiet her fears, they simply commanded her to stop screaming. But failing to obey their order, they then seized her and violently dragged her to the bathroom, where they plunged her into the bathtub of cold water.

This shock so convulsed her in agony that she now screamed louder than before. They then drowned her voice by strangulation, by holding her under the water until nearly dead… She promised she would not, but to make it a thorough ‘subduing,’ they plunged her several times after she had made them this promise…

This is what they call giving the patient a ‘good bath!’… The patient was then led, wet and shivering, to her room, and ordered to bed with the threat…” (1)

As late as the early 1900’s, women in asylums were subjected to electro-shock treatments, frontal lobotomies, and premature hysterectomies. (The word hysteria is Greek in origin; hustera or uterus. Hippocrates thought that madness in women occurred when the uteri had become dis-functional from lack of sexual intercourse and rose upward in the body compressing the heart, lungs and diaphragm. Hysterical symptoms would occur until the uterus dislodged itself.)

ELIZABETH PARSONS WARE AND HER FIGHT FOR WOMEN TO HAVE EQUAL PROTECTION UNDER THE LAW.

The Woman’s Movement actually began in the 1800’s, with such crusaders as Abigail Adams, wife of President John Adams, advocating for woman’s right to vote. The movement to gain a woman’s voting rights also petitioned for an end to slavery and prohibition of alcohol.

“In 1868, a few years after the Civil War, Congress passed the 14th Amendment to the Constitution which gave all U.S. citizens ‘equal protection of the laws’ and was aimed at partially presenting the southern states from trying to block former slaves from voting. But voters were defined as males. Then in 1870, the 15th Amendment was passed that guaranteed the right to vote to all voters, regardless of race ot color–but it did not mention women.”(2)

However, Elizabeth was not interested in voting rights or temperance. After her release from her three year confinement at the Jacksonville Asylum in Illinois, she began her crusade to gain protection for women who were accused of insanity or were property owners.

HER MARRIED LIFE.

Elizabeth was well educated and outspoken. She was married to Theopolius Packard on May 21, 1839. He was fifteen years her senior and her family probably considered him an ideal husband for the daughter of a minister; her father was Reverend Samuel Ware, of South Deerfield, Massachusetts.

Elizabeth and Theophlius had six children. They eventually moved to Manteno, Illinois. He was a Calvinist, but she began to openly challenge his beliefs. She became interested in Universalism, Phreulogy, Spiritualism and Swedenborgianism. They disagreed on child rearing, finances and slavery. She wanted to become a Methodist. He thought her insane and contrived to get her committed to the first hospital in Illinois for the mentally ill, at Jacksonville; established in 1851.

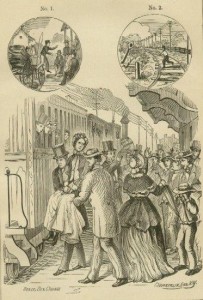

He arranged for a a doctor J.W. Brown to interview her under the pretense of being a salesman. Elizabeth complained to him of her husband’s dominance. She also told him she had heard of her husband speaking to others of her insanity. After the doctor relayed the conversation to Theophilus, the sheriff was sent for and she was escorted to court where she was pronounced insane.

During her imprisonment at Jacksonville, she was regularly questioned by doctors with regards to her sanity. She refused to agree she was insane or to change her her religion. She even contrived for her release, by pretending to fall in love with her doctor, Dr. Andrew McFarland, superintendent of the Asylum.

Eventually through the efforts of her children and her father she was released to her husband in June 1863. Theophilus locked her in her room and took away her clothes. Though he could have her committed to an insane asylum, it was illegal to keep her locked up in her house. She managed “to throw a letter out a window to a friend. A writ of habeas corpus was filed on her behalf.” (3)

At trial to regain her position of legal sanity, Theophilus’ lawyers produced witnesses from his family and congregation to say she had tried to withdraw from his church and that she argued with her husband. The Illinois State Hospital stated she was incurable, hence their reason for her release.

The lawyers for Elizabeth brought forth witnesses fromsthe community who stated they had never seen her argue with her husband or exhibit any traits of insanity. “The final witness was Dr. Duncanson, who was both a physician and an theologian. Dr. Duncanson had interviewed Elizabeth Packard and testified that while not necessarily in agreement with all her religious beliefs… ‘I do not call people insane because they differ with me. I pronounce her sane…’ ”

The jury took seven minutes to find in her favor and she was declared legally sane. (3)

“FATHER BECOMES MY PROTECTOR.

I therefore returned to my father’s house in Sunderland, and finding both of my dear parents feeble and in need of some one to care for them, and finding myself in need of a season of rest and quiet, I accepted their kind invitation to make their house my home for the present. At this point my father indicated his true position in relation to my interests, by his self moved efforts in my behalf in writing and sending the following letter to Mr. Packard.

‘Sunderland, Sept. 2, 1865.

REV, SIR : I think the time has fully come for you to give up to Elizabeth her clothes. Whatever reason might have existed to justify you in retaining them, has in process of time, entirely vanished. There is not a shadow of excuse for retaining them. It is my presumption there is not an individual in this town who would justify you in retaining them a single day.

Elizabeth is about to make a home at my house, and I must be her protector. She is very destitute of clothing, and greatly needs all those articles which are hers.

I hope to hear from you soon, before I shall be constrained to take another step.

Yours Respectfully, REV. T. PACKARD.

SAMUEL WARE.’

The result of this letter was, that in about twenty-four hours after the letter was delivered, Mr. Packard brought the greater part of my wardrobe and delivered it into the hands of my father.” (4)

“REV. SAMUEL WARE’S CERTIFICATE TO THE PUBLIC.

This is to certify that the certificates which have appeared in public, in relation to my daughter’s sanity, were given upon its conviction the Mr. Packard’s own statements respecting her condition were true and were given wholly upon the authority of Mr. Packard’s own statements. I do, therefore, hereby certify, that it is now my opinion that Mr. Packard has had no cause for treating my daughter Elizabeth as an insane person.

SAMUEL WARE

Attest. {OLIVE WARE,

AUSTIN WARE.

SOUTH DEERFIELD, August 2, 1866.” (5)

Elizabeth never returned home and the Packard’s never divorced, but remained separated. A few weeks after the return of her clothing, Theophilus’ place in the pulpit had been replaced and he left the community.

Illinois repealed the 1851 statue making it easy to commit someone and by 1867, Illinois had returned to it’s tough standards of commitment by restoring the rights of women and children to a trial by jury to safeguard all persons, whatever their sex or economic status. Her case was reviewed by legislators in other states and similar laws were enacted there.

Elizabeth founded the Anti-Insane Asylum Society and published several books about her life in the asylum and the evils of other such institutions.”

Sources:

(1) “Mrs. Packard,” a play written and directed by Emily Mann, on-line at http://www.mccarter.org/Education/mrs-packard/html/7.html

(2) “Liberty: Woman’s History,” on-line at http://www.uen.orgthemepark/liberty/womanssuffrage.shtml

(3) “Elizabeth Packard,” on-line from Wikipedia at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Packard

(4) “Modern Persecution: Or Insane Asylums Unveiled,” Vol. 1, by Elizabeth Parsons Ware Packard, published by the Authoress, New York, 1873, page 225

(5) “The Private War of Mrs. Packard,” by Barbara Sapinsley, 1991, page 132

Other Sources: Tennessee Genealogical Society, Woman and the Insane Asylum, by Tina Sansone, TN Genealogy Society Member on-line at http://www.tngs.org/library/asylum.htm

Definition of Hysteria, on-line dictionary

Pingback: Mean Theophilus and his wife Elizabeth Parsons Ware, crusader for justice | Packed with Packards!

Pingback: Post #6: Exegesis – SHSU Dramaturgy (Mau)

During my lifetime I have never understood how any man, past or persent, could possibly treat a woman in this manner, especially his wife and the mother of his children. But then that was a different era. We don’t have to agree with it.

C. Wayne Ware

Cedar Falls, IA